Mastering Robotic Workcell Design: The Architectural Blueprint for CNC Machining Automation

Introduction: The Foundational Discipline of Modern Manufacturing – Why Robotic Workcell Design is the Critical Success Factor

In the intricate ecosystem of modern manufacturing, the automation of a CNC machining process is a symphony of precision engineering, systems integration, and operational foresight. While the allure of advanced robotics and high-speed spindles captures attention, the true determinant of success—where uptime, safety, and return on investment are either guaranteed or gambled—resides in the foundational discipline of robotic workcell design. This discipline transcends mere equipment arrangement; it is the comprehensive architectural and systems engineering process that transforms disparate components—a CNC mill, an industrial robot, a vision system, and material conveyors—into a single, cohesive, and high-performance production organism. A flawed robotic workcell design, regardless of the sophistication of its constituent parts, will manifest as chronic downtime, safety near-misses, and persistent bottlenecks. Conversely, a masterfully executed design yields a resilient, predictable, and scalable asset that operates with the reliable rhythm of a precision timepiece. For manufacturing engineers and operations leaders, proficiency in robotic workcell design is the indispensable skill that separates the implementation of automation from the achievement of autonomous, high-performance production.

At JLYPT, our worldview is sculpted at the confluence of precision machining and holistic system optimization. We perceive robotic workcell design as the essential engineering phase where theoretical efficiency is translated into tangible, shop-floor reality. It is a multidimensional challenge demanding the synthesis of mechanical kinematics, industrial ergonomics, control logic, and rigorous safety science. This guide is architected for the manufacturing professional—the engineer, the integrator, the manager—who recognizes that the “how” of system assembly is as consequential as the “what” of component selection. We will deconstruct the core principles of effective robotic workcell design, provide a phase-gated framework for its execution, and delve into the nuanced considerations that distinguish a merely functional cell from an exceptional one. Our objective is to furnish you with the conceptual tools and practical insights necessary to architect systems that don’t just automate a task, but fundamentally elevate your manufacturing capability.

Section 1: Foundational Tenets and Architectural Principles of Robotic Workcell Design

Before a single line is drawn in CAD, the robotic workcell design process must be governed by a set of inviolable principles. These tenets ensure the resultant system is inherently safe, operationally reliable, and economically viable.

1.1 The Hierarchy of Design Imperatives

-

Safety as the Non-Negotiable Foundation: Every design decision must originate from a risk assessment framework compliant with ISO 12100 (risk assessment) and ISO 10218-1/2 (robot safety). This extends beyond physical guarding to encompass functional safety in control logic, ensuring failsafe operation under all foreseeable fault conditions. The design must proactively protect personnel, the equipment, and the capital investment.

-

Reliability and Maintainability as Core Tenets: The cell must be engineered for sustained, high-availability operation. This mandates:

-

Proactive Serviceability: Ample, unobstructed access for maintenance technicians to perform routine servicing on robots, CNC tooling, and peripherals without complex disassembly.

-

Environmental Hardening: Selection of components with appropriate ingress protection (IP ratings) to withstand coolant mist, metallic particulates, and vibration inherent to machining environments.

-

Inherent Error Recovery: Designing sensor networks and logical pathways that enable the system to detect common faults (e.g., part misload, gripper slip) and execute predefined recovery routines, minimizing unscheduled downtime.

-

-

Performance and Throughput as Engineered Outcomes: Only upon the bedrock of safety and reliability can the focus shift to optimizing cycle time and output. This involves meticulous path optimization, minimizing non-value-added robot travel, and ensuring seamless synchronization between the robot and the CNC machine’s processing cycle.

1.2 The Integrated System Architecture

A holistic robotic workcell design integrates several interdependent subsystems into a unified whole:

-

Primary Processing Station: The CNC machine tool, with its specific work envelope, door/chuck actuation mechanisms, and control interface (e.g., Fanuc, Siemens, Heidenhain).

-

Material Handling Robot: The articulated, SCARA, or gantry robot selected for its payload, reach, repeatability, and speed characteristics.

-

Material Flow and Buffering System: The mechanism for presenting raw workpieces and evacuating finished parts. This can range from simple conveyors and rotary index tables to complex Automated Storage and Retrieval Systems (ASRS) or AGV interfaces.

-

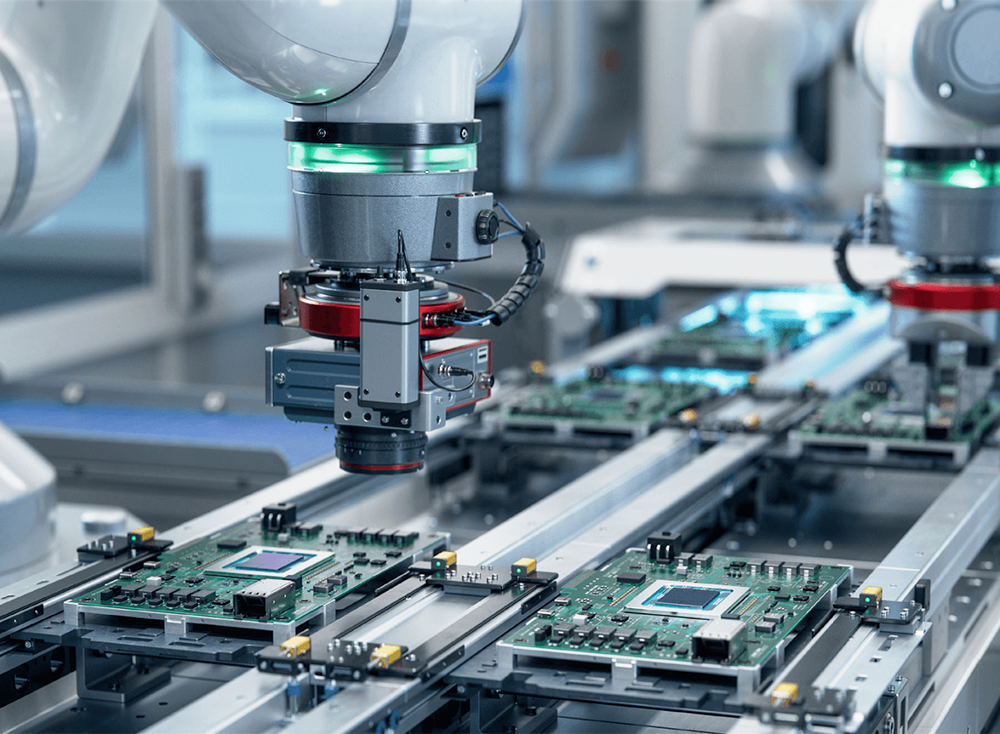

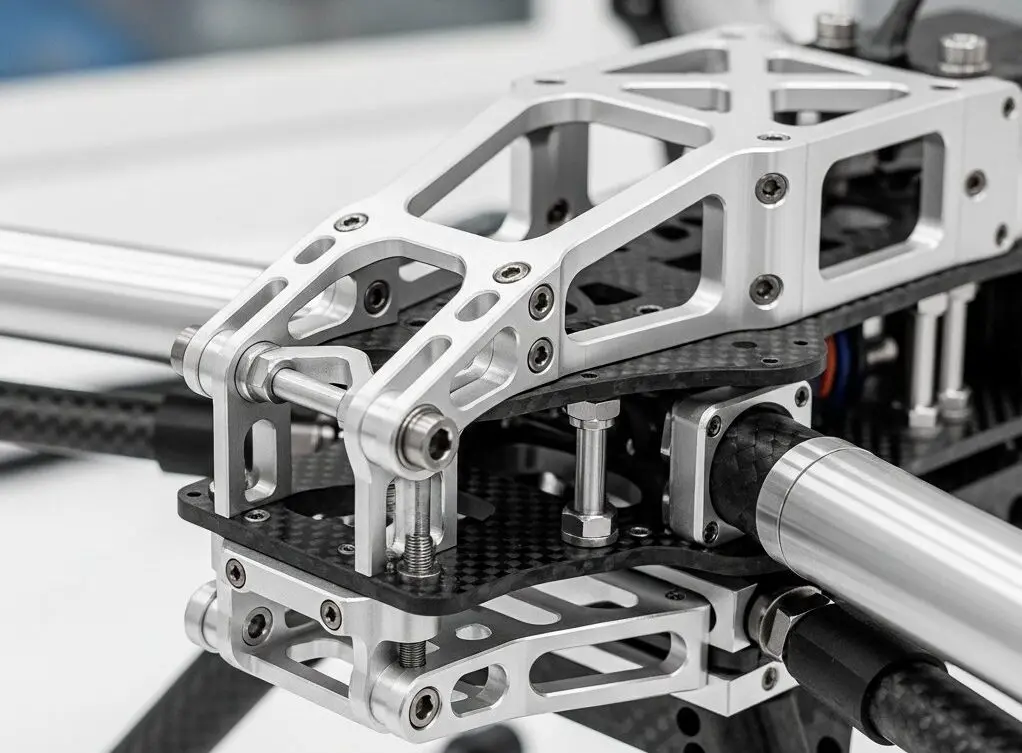

End-of-Arm Tooling (EOAT): The custom-engineered interface—be it a mechanical gripper, vacuum head, or magnetic handler—that physically interacts with the workpiece. Its design is critical for part safety and positioning accuracy.

-

Precision Tooling and Fixturing: The custom workholding solutions that secure parts within the CNC machine and often within staging areas. The repeatability of these fixtures, often produced using JLYPT’s high-precision machining capabilities, is paramount to overall system accuracy.

-

Peripheral Support Systems: Essential ancillaries including chip conveyors, coolant filtration and delivery systems, mist collectors, and part washing stations.

-

Control and Safety System Architecture: The Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) that sequences operations, the Human-Machine Interface (HMI) for operator interaction, and all safety-rated components (light curtains, safety relays, area scanners).

-

Sensing and Metrology Layer: Vision systems, laser profilers, and touch probes that provide the cell with situational awareness for adaptive operation and in-process verification.

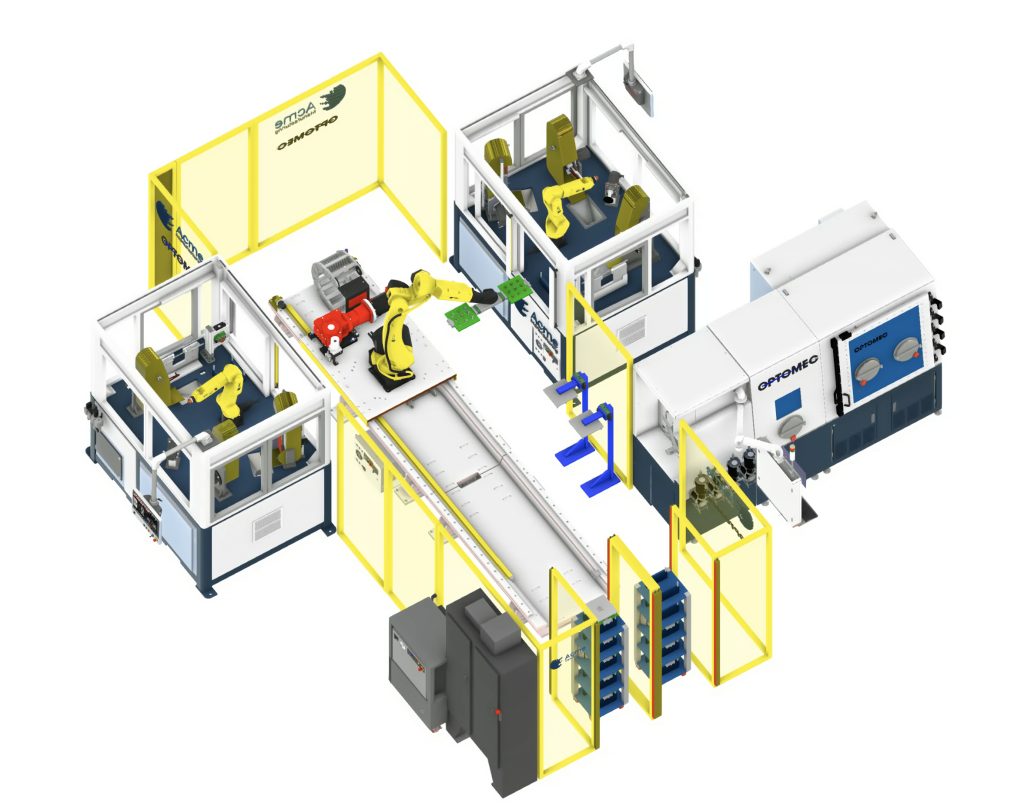

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Robotic Workcell Design Layout Archetypes

| Layout Archetype | Description & Configuration | Primary Advantages | Primary Disadvantages | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Single Machine Cell | One robot services a single CNC machine, typically with inline conveyors for infeed/outfeed. | Low complexity, minimal footprint, simplified programming and debugging, lower initial capital cost. | Low robot utilization (robot idle during machine cycle); limited scalability; not suited for high-volume demands. | Introductory automation, long-cycle-time parts, low-volume or prototype production where robot idle time is acceptable. |

| Multi-Machine Servicing (Linear Rail) | A single robot mounted on a precision linear track (7th axis) services 2-4 CNC machines arranged in a line. | High robot asset utilization; capital cost of robot distributed across multiple machines; efficient floor space use. | Increased control complexity; critical dependence on rail alignment and reliability; robot failure halts all machines. | High-volume production lines with similar machines and part families. Maximizes ROI in automotive or consumer electronics sectors. |

| Pallet Pool / Flexible Manufacturing System (FMS) | Robot(s) service a centralized matrix of pallets/fixtures. CNC machines feature automatic pallet changers (APCs). | Maximum flexibility and uptime; enables true 24/7 unmanned production; high buffer capacity; ideal for part mixing. | Very high capital investment; significant floor space requirement; complex software (FMS controller) needed. | High-mix or high-volume 24/7 production of families of parts. Aerospace, defense, and advanced job shops. |

| Mobile Collaborative Cell | A collaborative robot (cobot) on a mobile AGV or wheeled cart can be deployed to multiple workstations as needed. | Ultimate operational flexibility; low barrier to entry; safe co-working with humans; minimal fixed infrastructure. | Lower payload and speed limits; requires manual setup/re-teaching at each location; not for high-tempo dedicated production. | High-mix, very low-volume job shops; low-volume secondary operations (deburring, inspection); frequent process changeovers. |

| Gantry-Based Overhead Cell | A Cartesian (X-Y-Z) robot is mounted on an overhead gantry framework, servicing machines and stations below. | Exceptional work envelope coverage; ability to handle very large, heavy parts; frees up valuable floor space. | Generally slower than articulated arms; potential for lower rigidity; requires significant overhead structural support. | Handling large monolithic parts (airframe components, mold bases). Cells integrating multiple process islands (machining, washing, CMM) under one gantry. |

Section 2: A Phase-Gated Framework for Systematic Robotic Workcell Design

Adhering to a structured methodology mitigates project risk and ensures comprehensive coverage of all critical design facets.

Phase 1: Discovery, Analysis, and Requirements Definition

This phase solidifies the “why” and quantifies the “what.”

-

Granular Process Mapping: Document the existing manual process with time-motion studies, video analysis, and value-stream mapping to identify all non-value-added activities.

-

Comprehensive Part Family Analysis: Catalog all intended parts: 3D models, weights, materials, batch sizes, annual volumes, and most critically, identifiable features suitable for robotic gripping and CNC fixturing.

-

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking: Establish clear, measurable Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that will define project success. Examples include:

-

Target OEE improvement (e.g., from 65% to 88%).

-

Direct labor reduction (e.g., 2.0 FTE per shift).

-

Required throughput rate (parts per hour).

-

Maximum permissible payback period (e.g., ≤ 22 months).

-

Phase 2: Conceptual Design, Simulation, and Virtual Validation

This phase develops and stress-tests the “how” in a digital environment.

-

Conceptual Layout Development: Generate 2-3 distinct layout concepts based on the archetypes in Table 1. Evaluate each against metrics of flow, footprint, and future expandability.

-

Digital Twin Creation & Cycle Time Simulation: Utilizing offline programming and simulation software (e.g., RoboDK, Siemens Process Simulate), construct a dynamic digital twin of the proposed cell. This enables:

-

Kinematic Validation: Confirming the robot can reach all required points without joint limit violations or collisions with machinery, fences, or itself.

-

Cycle Time Optimization: Iteratively refining robot trajectories, wait points, and accelerations to minimize the overall work cycle. The simulation will conclusively identify whether the robot or the CNC process is the bottleneck.

-

Ergonomic and Maintenance Access Review: Virtually simulating human interaction for loading, unloading, and maintenance tasks.

-

-

Preliminary Risk Assessment: Identifying potential safety hazards and single points of failure at the conceptual stage.

Phase 3: Detailed Engineering Design and Documentation

This phase transforms the validated concept into manufacturable and executable instructions.

-

Mechanical Design Finalization: Production of detailed drawings for all custom components: robot pedestals, safety fencing, custom grippers, fixture bodies, and conveyor frames. This includes specifying materials, tolerances, and surface finishes.

-

Electrical and Control System Design: Creation of complete electrical schematics, pneumatic/hydraulic diagrams, panel layouts, and the PLC/HMI software architecture. Definitive communication protocols between the robot and CNC (e.g., Profinet signal mapping) are established.

-

Safety System Design Certification: Final design of the safety circuit to meet ISO 13849-1 Performance Level d (PLd) or e (PLe). Specification of all safety devices: safety PLC, muting sensors for material gates, emergency stops, and configured safe zones within the robot controller.

Section 3: Critical Design Considerations for the CNC Machining Environment

A machine shop presents unique operational challenges that must be engineered into the robotic workcell design.

Mitigating Contamination and Ensuring Durability

Coolant, oil, and abrasive chips are pervasive adversaries.

-

Hardened Component Selection: Specify robots, grippers, and sensors with minimum IP65 (dust-tight and protected against water jets) ratings. IP67 is preferable for areas subject to washdown or heavy coolant exposure.

-

Integrated Chip and Coolant Management: Design cell flooring with graded drainage. Incorporate automated chip conveyors with integrated crushers or drag-out systems. Utilize protective bellows on robot wrist axes and way covers on linear rails.

-

Gripper Design for Hostile Environments: Design gripper jaws with smooth, chamfered profiles that shed chips. Avoid internal cavities or complex mechanisms that can trap debris and fail.

Engineering for Micron-Level Precision Interfaces

The robotic workcell design must ensure the robot presents the part to the CNC fixture with sub-millimeter accuracy.

-

Kinematic Coupling Integration: Employ hardened and ground tooling balls (ISO 9409-1) or diamond-pin locators at the interface between the robot’s EOAT and the machine fixture to achieve highly repeatable mechanical alignment.

-

Passive Compliance Integration: Incorporate a compliant device (spring-loaded or elastomer-mounted) between the robot flange and the gripper. This allows for minor axial or radial misalignment during part insertion, preventing jamming and component damage—a principle known as Remote Center Compliance (RCC).

-

Positive Feedback Loops: Integrate simple but robust sensors—inductive prox, laser distance—to provide binary confirmation of “part present” and “part fully seated” before allowing the CNC cycle to commence.

Designing for the Human-in-the-Loop

Even highly automated cells require human interaction for oversight, replenishment, and exception handling.

-

Ergonomic Staging Areas: Design manual load/unload stations at ergonomic heights (per ANSI/HFES 100) to minimize worker fatigue and risk of musculoskeletal disorders.

-

Intuitive HMI and Diagnostic Systems: The HMI must provide an at-a-glance cell status and guided troubleshooting. It should answer: “What fault occurred?” “Where is it?” and “What is the recovery procedure?”

-

Safe Maintenance Mode Integration: Design the safety system to permit a protected “maintenance mode” or “limited speed mode” (per ISO 10218) that allows technicians to safely enter the cell for tasks like gripper jaw changeovers or sensor adjustment.

Table 2: Robotic Workcell Design Validation and Acceptance Criteria Checklist

| Design Validation Category | Specific Requirement / Metric | Method of Verification | Acceptance Criteria / Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety System Compliance | Full compliance with ISO 10218-1/2 & ISO 13849-1 PLd. | Third-party safety audit; review of safety function logic diagrams and risk assessment documentation. | Zero Category 1 or 2 hazards identified. All safety functions operate as specified under test. |

| Cycle Time Performance | Average cycle time ≤ [X] seconds (part-out to part-in). | Timed measurement over 50 consecutive production cycles during Site Acceptance Test (SAT). | Achieved average is within 3% of the simulated cycle time target. |

| Positional Repeatability (3D) | Part placement accuracy within ±0.1mm in X, Y, Z. | Use of laser tracker or high-precision CMM to measure actual vs. programmed robot placement over 30 iterations. | All measured points fall within the specified volumetric tolerance sphere. |

| System Reliability (MTBF) | Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) > 500 hours. | Monitor over a 60-day production run post-SAT. Document all stoppages and root causes. | Calculated MTBF meets or exceeds target. No single point of failure causes >10% of downtime. |

| Part Handling Quality | Zero part damage attributable to cell handling. | Visual and tactile inspection of first 1,000 production parts run through the cell. | No scratches, dings, deformation, or surface contamination caused by gripper or transfer system. |

| Changeover Time (Flexibility) | Full changeover between Part A and Part B in ≤ [Y] minutes. | Timed, documented changeover performed by trained cell operator. Includes program load, fixture/gripper change, and first-part verification. | Time target met consistently over three consecutive changeover trials. |

| Maintenance Accessibility | All major service items accessible with standard tools within 15 minutes. | Verification by maintenance technician using a standardized checklist. | Confirmation that filters, gripper jaws, proximity sensors, and pneumatic valves can be accessed and replaced without major disassembly. |

Section 4: Case Studies – Principles of Robotic Workcell Design in Action

Case Study 1: High-Volume Automotive Component Manufacturing

-

Challenge: A Tier-1 supplier of aluminum transmission housings needed to achieve 24/7 production to meet contract volumes. Manual loading was a bottleneck, and machine utilization plateaued at 60%.

-

Robotic Workcell Design Solution: A multi-machine servicing layout was selected. A high-payload 6-axis robot was mounted on a hardened linear rail between three identical horizontal machining centers (HMCs). The robotic workcell design featured:

-

Centralized Dual-Buffer System: A servo-driven rotary table with dedicated stations for raw castings and finished parts.

-

Hydraulic Form-Fit Gripper: A custom gripper that located on two precision-machined datum bores, ensuring repeatable part orientation.

-

In-Cell Process Integration: An integrated blow-off station and part probe for first-article verification within the cycle.

-

Predictive Logic: The design included in-line weigh scales post-pick to detect a missed grip, initiating an automatic recovery routine.

-

-

Outcome: The cell achieved 93% OEE, enabling full lights-out operation for two shifts. The robot’s utilization exceeded 85%. The project achieved ROI in 16 months through direct labor savings and a 50% increase in output per square meter.

Case Study 2: Aerospace Turbine Component Finishing Cell

-

Challenge: Individual nickel-alloy turbine blades required a series of post-machining processes: laser marking, automated visual inspection, and final kitting. Manual handling between discrete stations was time-consuming and risked damage to the high-value components.

-

Robotic Workcell Design Solution: An overhead gantry-based cell was architected. A high-precision Cartesian robot traveled on X and Y axes above a large worktable containing four process islands. The robotic workcell design prioritized precision and contamination control:

-

Unified Tool Changer: The gantry incorporated an automatic tool changer to switch between a non-contact laser marker, a backlit vision inspection camera, and a vacuum end-effector.

-

Active Vibration Damping: The entire gantry superstructure was mounted on pneumatic vibration isolators to ensure inspection accuracy.

-

Modular Station Design: Each process station was a self-contained, plug-and-play unit with its own controller, facilitating easy future reconfiguration or technology upgrades.

-

-

Outcome: The cell created a continuous, hands-off flow, reducing blade throughput time by 70%. It eliminated three separate manual handling steps, provided a complete digital twin record for each blade (linking serial number to inspection data), and achieved a defect escape rate of near zero.

Case Study 3: Contract Machining Job Shop Flexible Automation Cell

-

Challenge: A job shop servicing the medical and aerospace sectors needed to improve the productivity of several 3-axis VMCs but faced a high part mix with low batch sizes, making dedicated automation economically unviable.

-

Robotic Workcell Design Solution: A flexible, mobile cell based on a collaborative robot was developed. The robotic workcell design focused on rapid redeployment and ease of use:

-

Mobile Integration Cart: The cobot, its controller, a pneumatic gripper, and a tooling rack were mounted on a lockable, wheeled cart with integrated pneumatic and electrical quick-disconnects.

-

Universal Machine Interface: A standard “soft jaw” vise system was installed on each VMC. The cobot was programmed with adaptive routines to handle a range of block-style parts.

-

Intuitive Graphical Programming: Shop machinists were trained to program new part routines using a simple “pick-point, place-point” graphical interface on a tablet in under 20 minutes.

-

-

Outcome: The cell provided a 30% average reduction in machine idle time across the shop floor. It allowed machinists to run multiple machines simultaneously and served as a low-risk introduction to automation. The flexibility justified the investment despite the high-mix environment.

Conclusion: Designing the Foundation for Manufacturing Resilience

The discipline of robotic workcell design is the critical linchpin between the procurement of automation technology and the realization of its full economic and operational potential. It demands a systems-thinking approach that harmonizes mechanical precision, control intelligence, human factors, and unwavering safety. A superior design yields a production asset characterized not just by functionality, but by resilience, maintainability, and built-in adaptability for future challenges.

The return on the investment of rigorous robotic workcell design is measured across the entire lifecycle of the system: in years of high uptime, in minimized operational overhead, and in the creation of a scalable platform for growth. It is the process that transforms a capital expenditure into a foundational manufacturing capability.

For organizations embarking on this complex journey, the expertise required is deep and multidisciplinary. Success is frequently accelerated by collaboration with partners who possess both granular knowledge of precision processes and a macro-level understanding of system integration. At JLYPT, our proficiency in producing high-tolerance components informs our approach to designing the interfaces and systems that must perform reliably at the heart of demanding production environments.

Ready to architect a robotic workcell that delivers sustained, high-performance automation for your CNC operations? Contact JLYPT to initiate a collaborative design review. Discover our systematic approach to manufacturing excellence at JLYPT CNC Machining Services.