Robotic Cell Layout Design: The Foundational Blueprint for High-Performance CNC Automation

The integration of industrial robots into Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining environments is no longer a luxury but a strategic imperative for achieving superior productivity, flexibility, and quality. However, the success of this integration hinges on a critical, often under-appreciated, preliminary phase: the robotic cell layout design. A well-conceived layout is far more than an arrangement of equipment on the factory floor; it is a meticulously engineered blueprint that dictates the cell’s safety, throughput, reliability, and future scalability. For a precision CNC machining service provider like JLYPT, mastering the science and art of robotic cell layout design is fundamental to delivering automation solutions that are not only powerful but also inherently robust, efficient, and capable of delivering a sustained return on investment.

This comprehensive guide will delve into the intricate principles of designing an optimal robotic machining cell. We will explore the key factors that influence layout decisions, from the fundamentals of robot kinematics and workspace analysis to advanced considerations of material flow, human interaction, and digital twin simulation. Through structured frameworks, detailed analyses, and real-world case studies, we will illustrate how a strategic approach to robotic cell layout design transforms a collection of machines into a cohesive, high-performance manufacturing unit.

1. The Strategic Imperative of Layout Design

A poorly designed robotic cell is a persistent source of operational friction. Its symptoms are low Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), frequent safety near-misses, excessive work-in-progress (WIP), difficult maintenance access, and an inability to adapt to new parts or processes. The costs are measured in lost production, high operational stress, and a failure to realize the promised benefits of automation.

Conversely, a scientifically optimized layout provides a multitude of strategic advantages:

-

Maximized Throughput and OEE: By minimizing non-value-added robot travel and optimizing the sequence of operations, cycle times are reduced, and machine spindle utilization is maximized.

-

Enhanced Safety and Ergonomic Compliance: A layout designed with safety-first principles clearly segregates human and robot workspaces, ensures clear visibility, and provides safe access for maintenance and tool change, directly complying with standards like ISO 10218 and ANSI/RIA R15.06.

-

Inherent Flexibility and Scalability: A forward-thinking layout anticipates future needs, allowing for the addition of a second robot, an extra CNC machine, or an automated guided vehicle (AGV) interface without a complete cell overhaul.

-

Reduced Footprint and Optimized Flow: Efficient use of factory floor space, coupled with a logical, unidirectional flow of raw material to finished parts, reduces clutter, minimizes handling, and improves overall shop floor logistics.

2. Foundational Principles: Analyzing the Core Components

Every robotic cell layout design begins with a deep analysis of its constituent elements and their interactions.

2.1. The Workpiece and Process Analysis

The part and its machining process are the primary drivers of the layout.

-

Part Geometry and Dimensions: Size, weight, and center of gravity dictate the required robot payload and the design of end-of-arm tooling (EOAT) and fixtures.

-

Machining Sequence and Cycle Time: Understanding the CNC machine’s cycle (loading, machining, probing, unloading) is essential to synchronize robot actions and avoid idle time. A complex part requiring multiple setups or in-process measurement will demand a more sophisticated layout than a simple load/unload operation.

-

Material and Surface Finish Requirements: Handling cast iron billets versus polished aerospace aluminum requires different considerations for gripper design and potential contamination control.

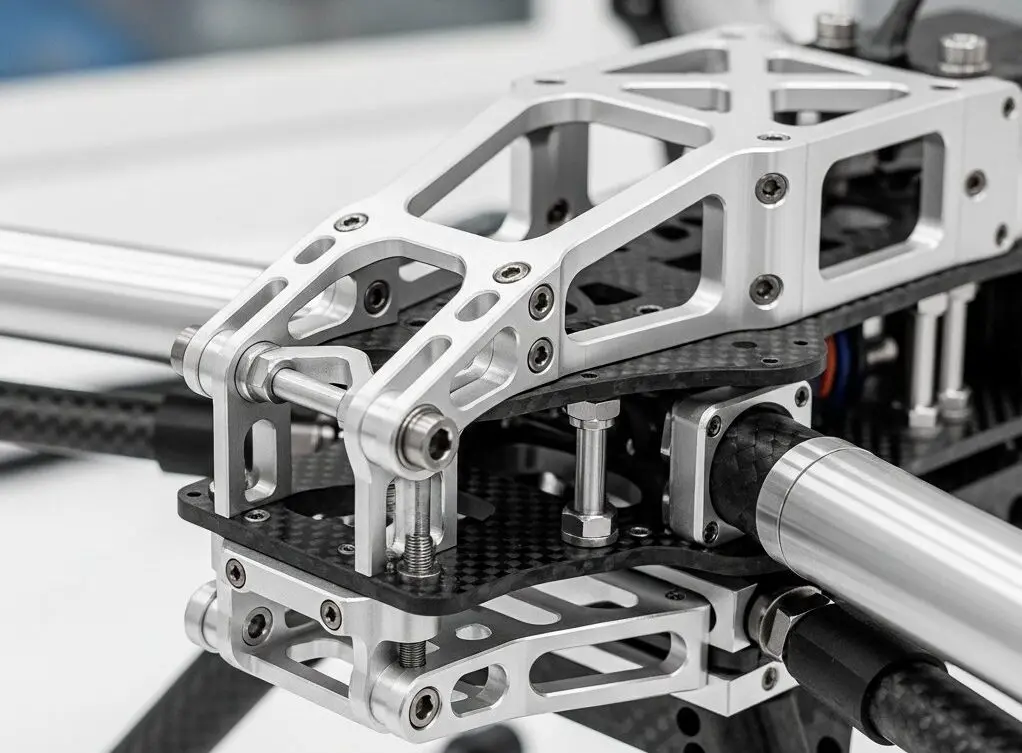

2.2. The Robot’s Kinematic Envelope and Performance

The robot is not a point in space but a volumetric entity with dynamic performance characteristics.

-

Reach and Work Envelope: The 3D space a robot can physically access defines the possible locations for machine doors, part presenters, and tool stands. Critical positions, like the machine chuck or a calibration station, must lie comfortably within this envelope, not at its extreme limits where accuracy degrades.

-

Payload and Inertia: The layout must account for the combined weight of the gripper, part, and any sensors. Mounting a heavy robot on a long linear track affects its dynamic performance and may require stiffer mounting foundations.

-

Robot Mounting Configuration: The choice between floor-mounted, wall-mounted, inverted (gantry), or rail-mounted robot drastically alters the layout geometry, floor space usage, and the robot’s effective work area.

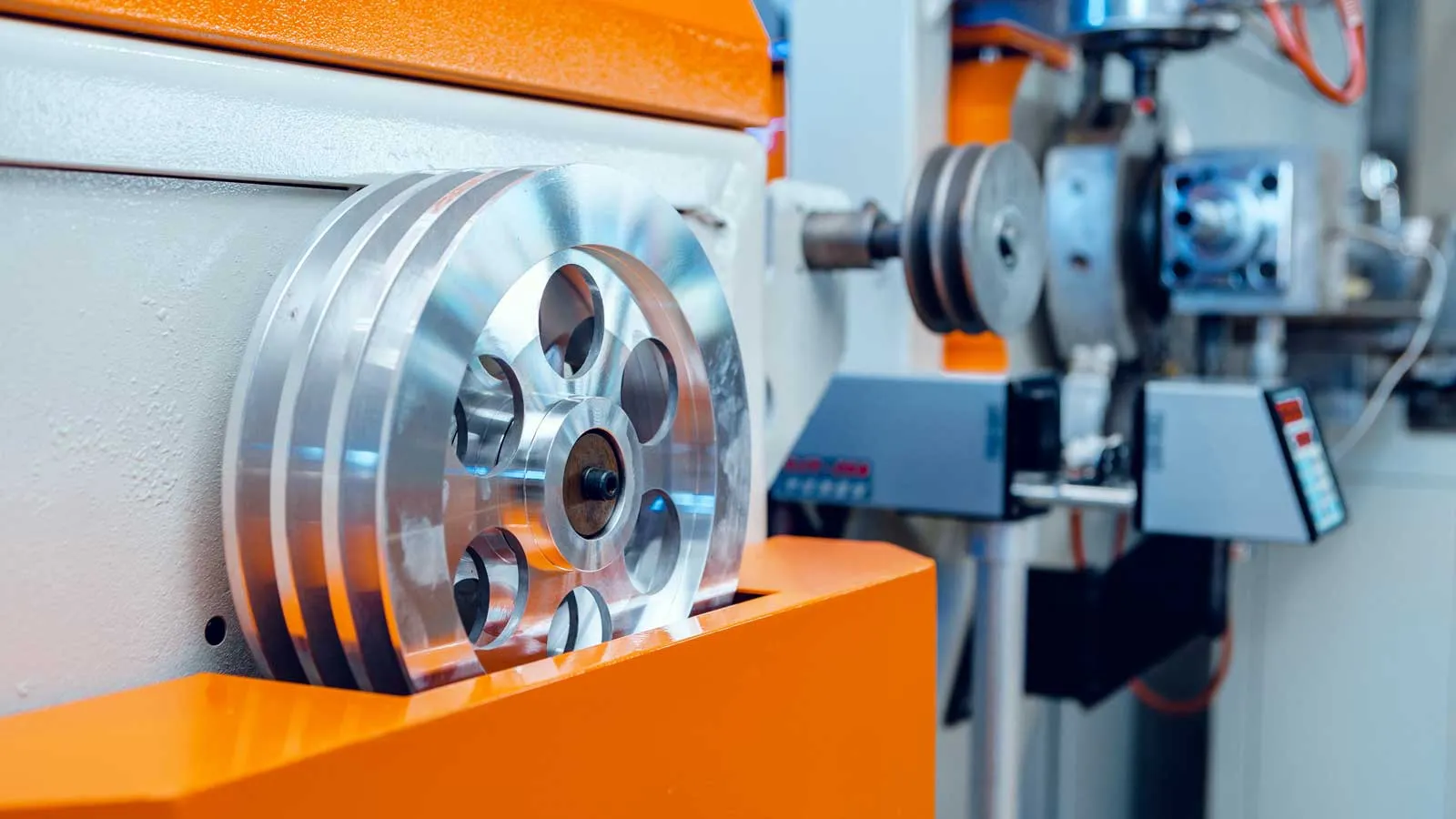

2.3. The CNC Machine and Peripheral Integration

The layout is the physical interface between the robot and the machining center.

-

Machine Door Access and Orientation: The design must ensure the robot can reliably reach the CNC table or chuck without interference from open doors, chip conveyors, or coolant systems. The orientation of the machine door (side, front, or L-shaped) is a key layout determinant.

-

Peripheral Systems Location: Essential peripherals like tool presetters, coolant filtration units, chip removal systems, and hydraulic power units must be positioned for easy service access without impinging on the robot’s operational space or safety zones.

3. Advanced Layout Strategies and Optimization

Beyond basic placement, advanced strategies are employed to maximize cell performance.

3.1. The Digital Twin and Simulation-Driven Design

Modern robotic cell layout design is executed virtually before any equipment is moved.

-

3D Collision Detection: Using software like RobotStudio, DELMIA, or Visual Components, engineers create a precise digital model of the entire cell. The robot’s programmed paths are simulated to detect and eliminate collisions with machines, fences, or other robots.

-

Cycle Time and Reachability Analysis: Simulation tools can calculate the total cycle time for a given layout and program, allowing engineers to test different robot speeds, travel paths, and equipment placements to find the most efficient configuration.

-

Ergonomics and Maintenance Validation: The digital twin allows for human avatars to perform tasks like manual load, tool change, or cell entry, ensuring these actions are safe and ergonomic in the proposed layout.

3.2. Material Flow and Logistics Integration

The layout must facilitate a smooth, logical flow of materials.

-

Infeed and Outfeed Strategies: Will raw material arrive on pallets, in bins, or via conveyor? Will finished parts be placed onto a different pallet, a conveyor, or directly into a washing station? The layout must define these flows. Common patterns include linear flow (in one side, out the other), U-shaped flow, or circular flow around a central robot.

-

Buffer and Queue Management: Where do parts wait before loading or after unloading? Smart layouts incorporate small buffer queues (e.g., a dual-station pallet stand) to decouple the robot’s cycle from upstream/downstream variability, preventing bottlenecks.

3.3. Safety Zoning and Human-Robot Collaboration (HRC) Layouts

Safety is not added; it is architected into the layout from the start.

-

Risk Assessment and Zoning: A formal risk assessment identifies hazards. The layout then defines safeguarded spaces (behind fences), operational spaces (where the robot works automatically), and collaborative workspaces where humans and robots can interact.

-

HRC Layout Principles: For collaborative applications, the layout ensures the robot’s restricted speed and force-monitored operations occur in a defined zone. It positions manual workstations, tool racks, and inspection areas to allow safe, efficient hand-offs between human and robot, often using pressure-sensitive floors or laser scanners for presence detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Robotic Cell Layout Archetypes for CNC Machining

| Layout Archetype | Description & Typical Configuration | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages / Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Robot, Single Machine (Island Cell) | One robot dedicated to loading/unloading one CNC machine. Often includes a part presenter/stand. | Simple, low-cost, easy to program and maintain. Minimal footprint. | Low robot utilization; bottleneck if CNC cycle is long. Ideal for proving automation concepts or very long machining cycles. |

| Single Robot, Multiple Machines (Tending Cell) | One robot (often on a linear rail) services 2-4 CNC machines in a line or cluster. | High robot utilization. Balances CNC and robot cycle times effectively. Reduces labor per machine. | Higher complexity in programming and scheduling. Rail adds cost and requires precise alignment. Excellent for high-volume, similar parts. |

| Multi-Robot, Multi-Machine (Synchronized Cell) | Multiple robots work in a coordinated fashion, possibly with a central pallet handling system or conveyor. | Maximum throughput and flexibility. Enables complex processes (machine, wash, inspect). | High capital cost. Extremely complex programming and safety integration. Requires sophisticated control (PLC/PAC). For large-scale, high-mix production. |

| Mobile Robot with Machining Unit | A robot (often collaborative) is mounted on a mobile AGV platform that docks with different machining stations. | Ultimate flexibility. Robot becomes a shared resource for multiple work cells. Minimal fixed infrastructure. | Challenging positioning accuracy at dock. Cycle time limited by travel. Safety protocols for mobile automation are complex. Ideal for low-volume, high-variety job shops. |

4. Critical Design Considerations for Precision Machining Cells

Specific to CNC machining, several factors demand special attention in the robotic cell layout design.

4.1. Accuracy and Repeatability Assurance

A robot’s positional accuracy can be influenced by its location and mounting.

-

Foundation and Vibration: The robot base and any linear track must be mounted on a stable, level foundation, isolated from vibrations transmitted by nearby CNC machines or forklift traffic.

-

Thermal Management: Layout should avoid placing the robot controller or robot arm in the direct path of heat from CNC machine chillers or ovens, which can cause thermal drift and positional error.

4.2. Integration of Metrology and Inspection

In-process quality control is a key advantage of automation.

-

Probe and Vision System Placement: Touch probes for part setup or tool breakage detection, and vision systems for part verification, must be positioned within the robot’s reach. Their location must be stable, clean, and free from coolant splash or chip accumulation.

4.3. Managing the Hostile Environment

Machining generates chips, coolant mist, and vibrations.

-

Chip and Coolant Management: The layout must ensure that robot wrists, joints, and sensors are protected from direct coolant spray. Chip conveyors should be routed away from robot bases and cables. Options include protective sleeves, positive-pressure enclosures, or locating the entire robot outside a sealed guarding enclosure, using a through-the-wall mount.

5. Case Studies: Layout Design Principles in Action

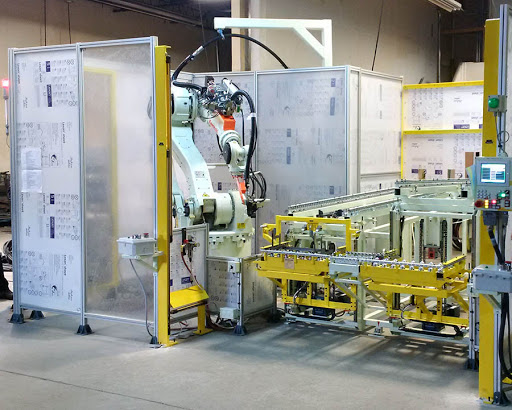

Case Study 1: High-Volume Automotive Transmission Housing Machining

-

Challenge: Machine 4 sides of an aluminum transmission housing across two 5-axis machining centers. Manual loading was slow and ergonomically taxing. Floor space was constrained.

-

Layout Design Solution: JLYPT engineers designed a compact “U-Shaped” Single Robot, Multiple Machines cell. A heavy-payload robot was mounted on a robust linear rail spanning the front of both machines. A central, dual-station rotary table served as the part presenter. The raw casting was manually loaded onto one side of the rotary table. The robot would pick, load into Machine 1 for first ops, transfer to Machine 2 for second ops, and finally place the finished part on the output side of the rotary table.

-

Outcome: The U-shaped flow minimized robot travel. The shared robot and centralized part handling maximized equipment utilization in a small footprint. OEE for both machines increased by over 40%, and manual handling was eliminated.

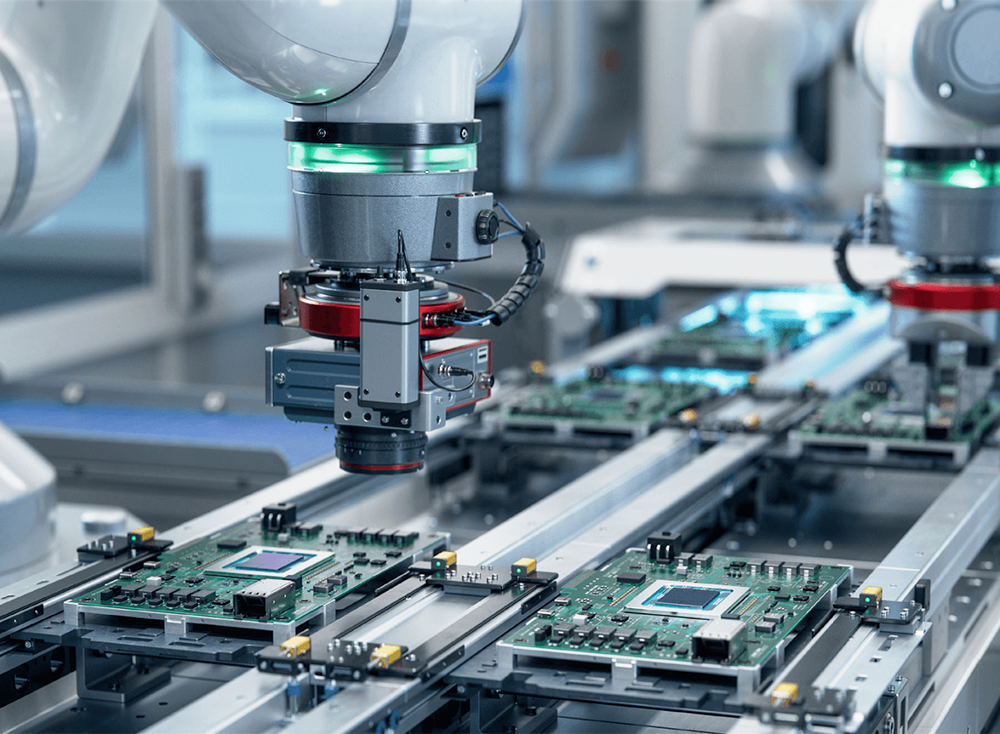

Case Study 2: Flexible Job Shop for Aerospace Brackets

-

Challenge: A job shop producing 50+ different titanium and aluminum brackets in low volumes needed automation but could not dedicate a robot to a single machine.

-

Layout Design Solution: The Mobile Robot with Machining Unit archetype was selected. A collaborative robot (cobot) with a force-sensitive gripper was mounted on a mobile, autonomous cart. The layout of the shop floor was modified to create standardized “dock stations” at two CNC mills and one CMM. The mobile unit would receive a work order, navigate to the raw material rack, pick a blank, dock at the specified CNC, load the part, and wait (or perform other tasks) until machining was complete.

-

Outcome: The flexible layout allowed one robot asset to service multiple machines, making automation economically viable for high-mix, low-volume production. Changeover between jobs was as simple as calling a new program.

Case Study 3: High-Precision Medical Implant Manufacturing Cell

-

Challenge: Machine and finish cobalt-chrome knee implants requiring a clean environment, in-process measurement, and absolute traceability. Any contamination or handling error was unacceptable.

-

Layout Design Solution: A Multi-Robot, Multi-Machine synchronized cell with a cleanroom enclosure. The layout featured a central, hermetically sealed enclosure. One robot dedicated to machine tending was mounted inside. A second, smaller robot for laser marking and final inspection was also inside. The layout included an automated airlock for part ingress/egress and integrated glove ports for manual override. All cabling and pneumatics entered from the top to keep the floor clear for cleaning.

-

Outcome: The layout created a controlled, clean environment. The segregated yet synchronized robot roles ensured a seamless flow from machining to marking to inspection without human intervention, guaranteeing the highest standards of quality and traceability.

6. The Implementation Roadmap: From Concept to Commissioned Cell

A successful transition from a layout diagram to a functioning cell follows a disciplined process:

-

Define Requirements and Constraints: Document part details, target cycle time, available floor space, utilities, and budget.

-

Create Initial Layout Concepts: Develop 2-3 high-level layout options (e.g., island vs. tending cell).

-

Develop the Digital Twin: Model the selected concept in 3D simulation software. Add all equipment, program robot paths, and run simulations to validate reach, detect collisions, and estimate cycle time.

-

Detailed Engineering Design: Based on the validated digital twin, create detailed mechanical drawings for foundations, mounting plates, safety fencing, and pneumatic/electrical raceways.

-

Factory Floor Preparation: Execute foundation work, run utilities (power, air, data), and install safety fencing per the layout drawings.

-

Installation, Commissioning, and SAT: Install equipment, calibrate the system, and perform a Site Acceptance Test (SAT) to prove the cell meets all performance specifications defined at the outset.

Conclusion: The Blueprint for Automated Excellence

In the world of automated CNC machining, success is not accidental; it is architected. The robotic cell layout design is the foundational blueprint that determines the operational DNA of the cell—its efficiency, safety, reliability, and capacity for growth. A strategic, simulation-driven approach to layout is what separates a problematic, underperforming installation from a transformative asset that delivers promised returns for years to come.

At JLYPT, we understand that precision extends beyond the cutting tool. It applies with equal rigor to the design of the manufacturing systems themselves. Our expertise in robotic cell layout design is rooted in a deep understanding of CNC processes, robot kinematics, and practical shop-floor realities. We engineer layouts that are not just feasible, but optimized for peak performance, ensuring our clients’ automation investments are built on a foundation of excellence.

Ready to architect the future of your machining operations with a professionally designed robotic cell? Contact JLYPT today to discuss how our systematic approach to robotic cell layout design can optimize your productivity and precision.