Introduction: The Interplay of Machinability and Environmental Durability in Brass Alloys

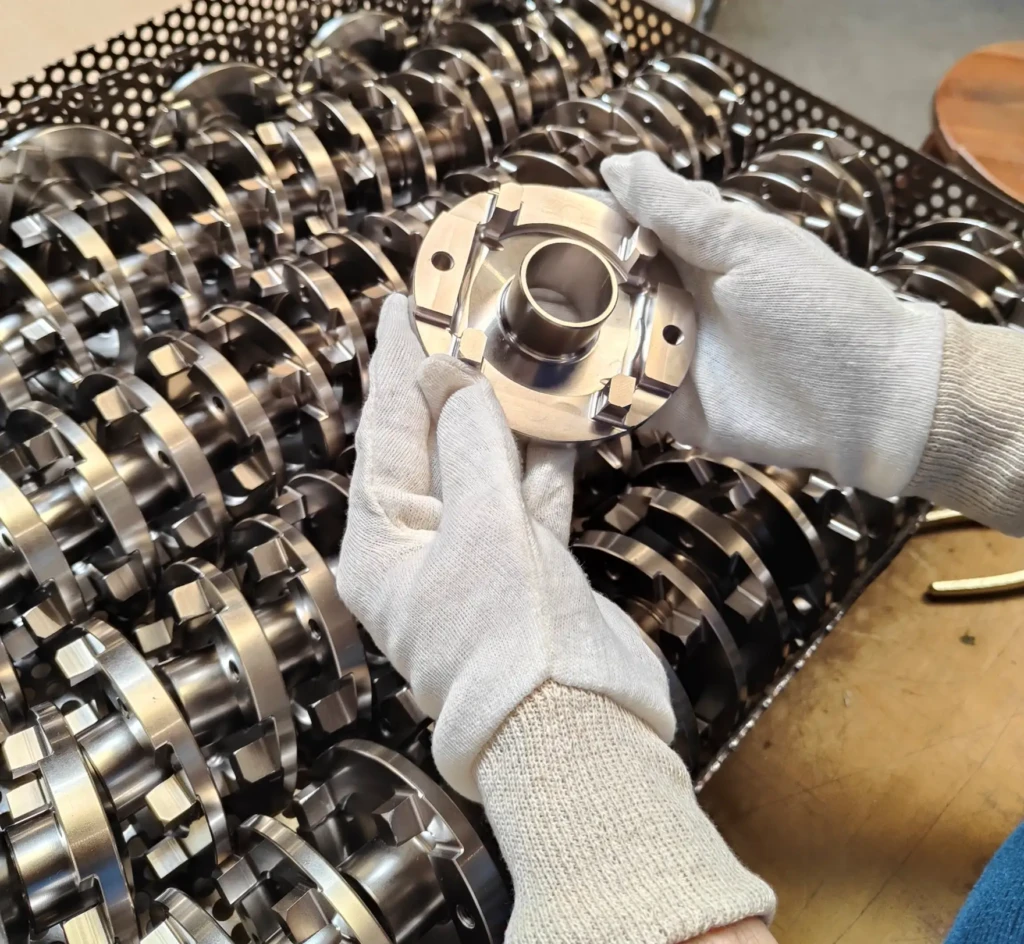

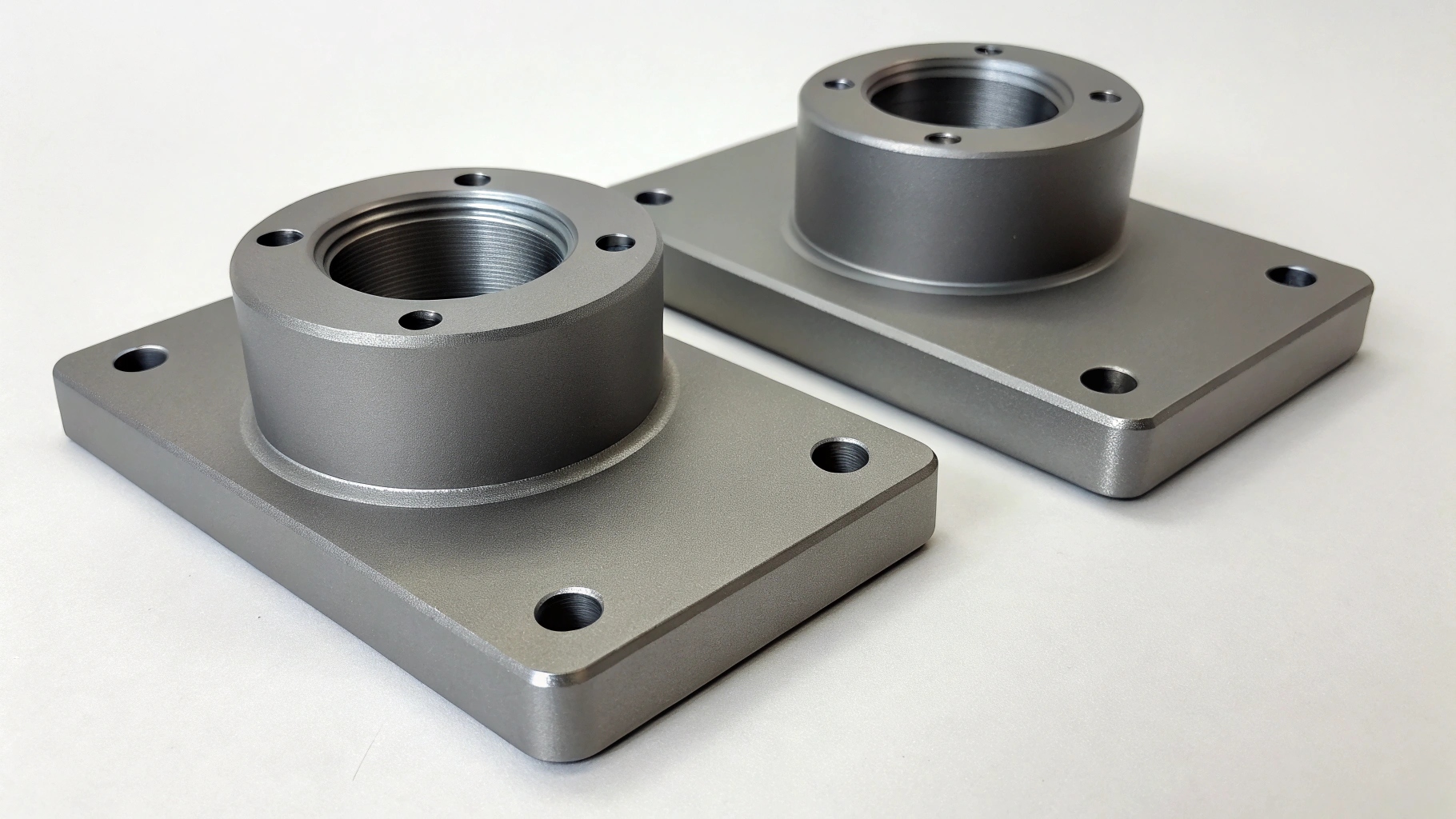

In the precision manufacturing landscape where material selection dictates both production efficiency and product lifespan, brass stands as a unique engineering alloy that bridges exceptional machinability with reliable environmental resistance. The fundamental question facing engineers and manufacturers isn’t whether brass offers corrosion resistance—it’s how the specific composition, microstructure, and CNC machining parameters interact to enhance or degrade this crucial property in finished components. At JLYPT CNC Machining, we’ve transformed countless brass billets into precision parts for marine, plumbing, musical instrument, and electrical applications, witnessing firsthand how machining decisions reverberate through a component’s service life.

Brass—a copper-zinc alloy system with potential additions of lead, tin, aluminum, or silicon—possesses what metallurgists term “inherent corrosion resistance” due to its copper content. However, this inherent resistance manifests differently across the dozens of standardized brass alloys, each with distinct electrochemical behaviors. The machining process itself introduces secondary factors: residual stresses, surface roughness, embedded tool particles, and even local microstructural changes that can create galvanic cells on a microscopic scale. True expertise in brass CNC machining corrosion resistance requires understanding these interactions at a fundamental level.

This comprehensive examination moves beyond generic material datasheets to explore the electrochemical mechanisms of brass corrosion, how specific machining operations alter surface integrity, and the post-processing treatments that can enhance durability. We’ll analyze how alloy selection (from free-machining C36000 to naval brass C46400) dictates both shop-floor efficiency and long-term performance in corrosive environments. For engineers specifying components for seawater exposure, chemical processing, or high-humidity applications, this knowledge is indispensable. Through detailed technical analysis and practical case studies, we demonstrate how strategic planning from initial stock selection to final finishing at our CNC machining services ensures brass components deliver both precision geometry and enduring performance.

The Electrochemical Fundamentals: How Brass Resists and Succumbs to Corrosion

To appreciate how CNC machining affects corrosion resistance, one must first understand brass’s fundamental corrosion mechanisms. Brass derives its baseline corrosion resistance from copper’s nobility in the electrochemical series and its ability to form protective surface films. When exposed to atmosphere, brass develops a thin layer of copper oxide and basic copper salts (patina) that inhibits further oxidation—a process significantly slower than iron’s rust formation.

Primary Corrosion Mechanisms in Brass:

-

Dezincification: The most metallurgically significant form of brass corrosion, particularly in alloys with zinc content above 15%. In this selective leaching process, zinc dissolves preferentially from the brass matrix, leaving behind a porous, copper-rich structure that retains the original shape but lacks mechanical strength. Dezincification occurs in stagnant or slowly moving waters, especially with high chloride content (seawater) or low pH. Alloys with added arsenic, antimony, or phosphorus (like C44300, Admiralty Brass) inhibit this process.

-

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC): A dangerous failure mode where brass under sustained tensile stress (often residual from machining or forming) fractures in specific corrosive environments, notably those containing ammonia or amines. The combination of stress and environment creates cracks that propagate through the material, often with little visible surface corrosion. SCC susceptibility increases with zinc content and is particularly relevant for cold-worked or highly stressed components.

-

Galvanic Corrosion: When brass electrically contacts a more noble metal (like stainless steel or titanium) in an electrolyte (like seawater), it can corrode preferentially as the anode in the galvanic couple. The reverse occurs when brass contacts less noble metals (like aluminum or steel), where brass acts as the cathode and is protected—though this accelerates corrosion of the coupled metal.

-

Erosion-Corrosion: The accelerated deterioration caused by combined chemical attack and mechanical abrasion from fast-moving fluids. This is particularly relevant for valve components, pump impellers, and marine fittings where high-velocity water or slurry flows across brass surfaces.

Table 1: Corrosion Mechanisms and Their Relevance to Machined Brass Components

| Corrosion Mechanism | Governing Electrochemical Principle | Most Vulnerable Brass Alloys | Common Service Environments | Machining-Related Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dezincification | Selective leaching of zinc from Cu-Zn matrix | High-zinc alloys (>20% Zn) without inhibitors | Stagnant/flowing seawater, acidic/soft fresh waters, soils | Surface roughness, embedded iron from tools, residual tensile stresses |

| Stress Corrosion Cracking | Combined tensile stress + specific corrodent | Alloys with >15% Zn, especially cold-worked conditions | Ammonia/amine atmospheres, mercury compounds, some industrial chemicals | Residual machining stresses, tool marks acting as stress concentrators |

| Galvanic Corrosion | Electrochemical potential difference in electrolyte | All brass alloys when coupled improperly | Marine environments, chemical plants with mixed-material assemblies | Introduction of dissimilar metal particles, poor post-machining cleaning |

| Erosion-Corrosion | Synergistic mechanical wear + chemical attack | All alloys in high-velocity applications | Pump components, valve seats, piping elbows, ship propellers | Surface finish quality, sharp edges vulnerable to cavitation, microstructure |

Brass Alloy Selection: Balancing Machinability and Corrosion Performance

The universe of brass alloys presents engineers with a spectrum where machinability and corrosion resistance often exist in inverse relationship. Understanding this trade-off is the first critical decision in designing durable brass components.

Free-Machining Brasses (C36000 Series):

The industry standard for complex components, C36000 (approximately 61.5% Cu, 3% Pb, balance Zn) offers unsurpassed machinability—rated 100% on the machinability index where free-cutting brass is the benchmark. The lead particles act as built-in chip breakers, reducing cutting forces and allowing for excellent surface finishes. However, lead’s presence creates several corrosion vulnerabilities: it forms galvanic couples with the copper-zinc matrix, potentially accelerating localized corrosion. Additionally, regulations like RoHS and the US Safe Drinking Water Act restrict leaded brass in potable water applications. For non-critical decorative components or applications without stringent environmental or regulatory demands, C36000 remains the productivity champion.

Naval and Admiralty Brasses (C46400, C44300 Series):

Engineered specifically for seawater service, these alloys incorporate 1% tin (C46400) or tin+arsenic/antimony (C44300). The tin addition forms a protective SnO₂ layer within the corrosion product film, dramatically inhibiting dezincification. Admiralty brass’s arsenic addition (0.02-0.06%) particularly suppresses selective zinc leaching. While significantly more corrosion-resistant, these alloys are tougher and gummier to machine than leaded brass, requiring modified tool geometries, reduced speeds, and potentially different coolant formulations. Their machinability rating falls to around 30% of C36000.

Silicon and Aluminum Brasses (C69400, C68700):

These alloys replace some zinc with silicon or aluminum, creating distinctive properties. Silicon brass (C69400) offers excellent corrosion resistance, particularly to dezincification, along with good strength and wear resistance. Aluminum brass (C68700, with ~2% Al) forms a particularly tenacious aluminum oxide surface film, providing outstanding resistance to impingement and erosion-corrosion in high-velocity seawater. From a machining standpoint, silicon brass machines reasonably well (similar to naval brass), while aluminum brass’s toughness presents greater challenges, often requiring specialized tool coatings like AlTiN to prevent built-up edge.

Choosing the Optimal Alloy:

The selection process should follow this hierarchy:

-

Identify the primary corrosion mechanism (e.g., seawater = dezincification risk)

-

Consider regulatory constraints (e.g., lead-free for drinking water)

-

Evaluate mechanical requirements (strength, wear)

-

Balance with production volume and complexity (high-volume complex parts benefit from higher machinability)

Table 2: Brass Alloy Selection Matrix for Corrosion Resistance vs. Machinability

| Brass Alloy (UNS) | Common Name | Key Alloying Elements | Corrosion Resistance Rating (1-10) | Primary Corrosion Strength | Machinability Rating (% of C36000) | Typical CNC Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C36000 | Free-Cutting Brass | Cu (61.5%), Pb (3.0%), Zn (bal.) | 3 | Atmospheric, mild environments | 100% (Benchmark) | Electrical connectors, decorative hardware, low-stress fittings |

| C26000 | Cartridge Brass | Cu (70%), Zn (30%) | 4 | Good general resistance, some dezincification risk | 80% | Ammunition components, springs, architectural trim |

| C46400 | Naval Brass | Cu (60%), Zn (39.25%), Sn (0.75%) | 8 | Excellent seawater resistance, inhibits dezincification | 30% | Marine hardware, propeller shafts, pump components |

| C44300 | Admiralty Brass | Cu (71%), Zn (28%, Sn (1%), As (0.06%) | 9 | Superior seawater resistance, arsenic inhibits dezincification | 25% | Heat exchanger tubes, condenser plates, marine systems |

| C48500 | Leaded Naval Brass | Cu (60%), Zn (37.5%), Pb (1.5%), Sn (1%) | 7.5 | Good seawater resistance with improved machinability | 50% | Complex marine valves, fittings requiring intricate machining |

| C69300 | Silicon Brass | Cu (81.5%), Zn (14.5%), Si (4%) | 8 | Excellent dezincification resistance, good wear resistance | 35% | Valve stems, architectural marine hardware, corrosion-resistant fasteners |

The Machining-Corrosion Interface: How Manufacturing Processes Alter Surface Integrity

CNC machining is not a neutral process regarding corrosion resistance. Every cutting operation modifies the brass surface in ways that influence its electrochemical behavior. The goal of corrosion-optimized machining is to produce a surface that is metallurgically clean, compressive-stressed, and free of defects that could initiate localized attack.

Surface Roughness and Area Effects:

The arithmetic average roughness (Ra) value directly correlates with corrosion susceptibility. A rougher surface has greater actual surface area exposed to the environment, providing more initiation sites for corrosion. More critically, deep grooves or tool marks can create crevices where electrolyte chemistry becomes stagnant and differs from the bulk solution—a perfect setup for crevice corrosion. For corrosion-critical applications, specifying a fine surface finish (Ra < 0.8 µm) and ensuring toolpaths avoid pronounced directional patterns are essential. High-feed finishing techniques or final roller burnishing can achieve both excellent finish and beneficial compressive stresses.

Residual Stress Profiles:

Machining induces complex stress fields in the subsurface layer. Typically, brass develops a thin, highly deformed layer with tensile residual stresses at the immediate surface, transitioning to compressive stresses slightly below. These tensile stresses are problematic as they can accelerate stress corrosion cracking. Process parameters significantly influence this: aggressive cuts with dull tools increase tensile stresses and deformation, while sharp tools with proper geometry and adequate coolant/lubrication produce a more favorable stress state. For highly susceptible applications, a post-machining low-temperature stress relief (around 250-300°C for 1-2 hours) can mitigate this risk without affecting mechanical properties.

Microstructural Alteration:

The extreme shear and heat at the tool-chip interface can alter the brass microstructure in the “white layer” or “affected zone.” In leaded brasses, lead particles may smear or redistribute. In alloys prone to dezincification, the heat can locally change phase distributions (α vs. β phase in Cu-Zn system), creating micro-galvanic cells. Using sharp tools, managing heat with appropriate coolant (often a sulfur-free mineral oil-based fluid for brass to prevent staining), and avoiding excessive tool wear are critical to preserving the base metal’s homogeneous microstructure.

Embedded Contaminants and Surface Cleanliness:

Perhaps the most overlooked factor is the potential for microscopic tool particle transfer. When machining brass with high-speed steel (HSS) or even carbide tools, tiny fragments of the tool material (iron, tungsten, cobalt) can become embedded in the softer brass surface. These foreign particles create potent sites for galvanic corrosion initiation. This phenomenon necessitates using dedicated, sharp tools for final finishing passes and implementing rigorous post-machining cleaning processes, often involving ultrasonic cleaning with appropriate solvents to remove all cutting fluids and particulate matter.

Optimized CNC Machining Parameters for Enhanced Corrosion Performance

Translating metallurgical principles into machine shop practices requires specific parameter adjustments. The following guidelines focus on producing brass components with optimal surface integrity for corrosion resistance.

Tooling Selection and Geometry:

-

Tool Material: For most brass machining, uncoated micro-grain carbide provides the best combination of sharpness, edge retention, and cost. PCD (polycrystalline diamond) tools offer the ultimate in edge sharpness and longevity, virtually eliminating built-up edge and providing the finest possible finish, but at a higher initial cost justified for high-volume production.

-

Geometry: Positive rake angles (10-15°) with highly polished flutes are essential to promote shearing rather than plowing. A large relief angle prevents rubbing against the machined surface. For drilling, high-spiral (quick spiral) drills designed for non-ferrous materials provide best chip evacuation and hole surface quality.

Cutting Parameters:

-

Speed (Vc): Brass machines efficiently at high speeds. For C36000, surface speeds of 200-400 m/min are typical. For tougher alloys like naval brass, reduce to 100-200 m/min. The key is to maintain a speed high enough to generate heat in the shear zone for proper chip formation but not so high as to cause excessive workpiece heating.

-

Feed Rate: Maintain an adequately high feed per tooth (0.1-0.2 mm/rev for milling, 0.05-0.15 mm/rev for turning). Light feeds cause rubbing, work hardening, and increased tensile residual stresses.

-

Depth of Cut: Favor moderate depths of cut. Too shallow risks rubbing; too aggressive increases cutting forces and potential distortion. A finishing pass of 0.1-0.25 mm is typically sufficient to remove the disturbed layer from previous operations.

Coolant and Lubrication Strategy:

The choice between dry machining, air blast, or wet coolant depends on the operation and alloy.

-

Dry Machining: Acceptable for many operations with sharp tools and good chip evacuation, eliminating post-cleaning of coolant residues. Monitor carefully for heat buildup.

-

Compressed Air Blast: Excellent for chip removal and slight cooling without introducing chemical contaminants. Often ideal for final finishing passes.

-

Wet Coolant/Lubricant: Necessary for high-production environments, deep-hole drilling, or tough alloys. Use a sulfur-free, non-staining, mineral oil-based fluid specifically formulated for non-ferrous metals. Water-soluble synthetic fluids can be used but must be monitored for pH to prevent staining. Never use chlorine-containing additives, as chlorides can initiate pitting corrosion.

Post-Machining Treatments for Maximum Durability:

-

Mechanical Surface Enhancement: Processes like vibratory finishing, tumbling, or micro-bead blasting with glass beads can homogenize surface roughness, impart beneficial compressive stresses, and remove microscopic peaks that are corrosion initiation sites.

-

Chemical Passivation: While more common for stainless steel, certain chemical treatments can enhance brass’s natural oxide layer. Dilute benzotriazole (BTA) solutions form a protective molecular film on copper alloys, significantly inhibiting tarnishing and certain corrosion forms. This is particularly valuable for decorative or electrical components.

-

Electroplating/Coating: For extreme environments, electroplated layers of nickel, chromium, or tin provide a sacrificial or barrier coating. For marine applications, a electroless nickel-phosphorus plating offers excellent uniformity and corrosion resistance even on complex geometries.

-

Clear Coating: For architectural or decorative brass where patina (natural tarnishing) is undesirable, high-quality acrylic or polyurethane clear coats provide a durable barrier against moisture and atmospheric pollutants while maintaining the brass’s appearance.

Industry Case Studies: Applied Corrosion Resistance Solutions

Case Study 1: High-Pressure Marine Valve System (Seawater Service)

-

Challenge: A manufacturer of underwater remotely operated vehicle (ROV) systems required a complex multi-port manifold valve body operating at 3000 psi in full seawater exposure. The design involved intersecting bores and threaded ports that created numerous crevice geometries vulnerable to corrosion.

-

Material & Process Selection: C46400 (Naval Brass) was selected for its proven seawater corrosion resistance. The primary challenge was machining the intricate internal passages without compromising the alloy’s inherent properties through excessive heat or tensile stresses.

-

JLYPT Solution: We employed a multi-stage machining strategy:

-

Roughing with dedicated tools to remove bulk material.

-

Stress-relief thermal cycle to normalize the part.

-

Semi-finishing of all critical surfaces.

-

Final finishing with sharp, PCD-tipped boring tools and reamers, using a non-chlorinated, oil-based cutting fluid maintained at precise concentration.

-

Post-machining, all components underwent ultrasonic cleaning in an alkaline solution followed by a deionized water rinse and hot air drying to eliminate any electrolyte residue.

-

A final micro-bead blast with 50-micron glass beads applied a uniform matte finish and compressive surface stress.

-

-

Result: The valve bodies passed a 90-day accelerated salt spray (ASTM B117) test with zero signs of dezincification or crevice corrosion at threaded interfaces and have performed flawlessly in field operation for over three years.

Case Study 2: Potable Water Metering Component (Lead-Free Regulatory Compliance)

-

Challenge: A supplier to the municipal water industry needed to redesign a legacy brass water meter body to comply with the updated Safe Drinking Water Act, reducing lead content to a weighted average of 0.25% across wetted surfaces. The component required excellent machinability for high-volume production and corrosion resistance to varied water chemistries across different municipalities.

-

Material & Process Selection: C69300 (Silicon Brass – 81.5% Cu, 14.5% Zn, 4% Si) was chosen as the lead-free alternative. While corrosion-resistant and dezincification-resistant, its machinability is significantly lower than leaded brass.

-

JLYPT Solution: We redesigned the machining process from the ground up:

-

Optimized tool geometries with higher positive rake and specialized chip-breaker patterns for the stringy chips characteristic of silicon brass.

-

Implemented high-pressure through-tool coolant to manage heat and improve chip evacuation in deep boring operations.

-

Adjusted all speeds and feeds based on extensive testing to balance tool life and surface integrity.

-

Introduced a final roller burnishing operation on critical sealing bores to achieve a mirror-like finish (Ra < 0.2 µm) that minimized surface area and potential for scaling or biofilm adhesion.

-

-

Result: The components met all lead-leachate requirements (tested via NSF/ANSI 61), achieved a 30% longer tool life than initial projections, and demonstrated superior corrosion resistance in accelerated testing with aggressive (soft, acidic) water compared to the previous leaded alloy design.

Case Study 3: Architectural Facade Fastener System (Atmospheric & Aesthetic)

-

Challenge: An architectural firm specified custom brass fasteners for a prominent coastal building facade. The fasteners needed to maintain structural integrity for decades while developing a consistent, attractive patina rather than unsightly localized corrosion or staining that could streak the limestone cladding.

-

Material & Process Selection: C26000 (Cartridge Brass) was selected for its good balance of corrosion resistance, strength, and cost. The key was controlling the corrosion process to be uniform and predictable.

-

JLYPT Solution: Precision machining was followed by a carefully engineered surface preparation:

-

All fasteners were machined to a consistent fine finish (Ra 0.4 µm).

-

They underwent a chemical cleaning process to remove all machining oils and fingerprints.

-

A deliberate artificial patination process was applied using a controlled chemical treatment (typically a liver of sulfur solution) to accelerate the formation of a stable, uniform copper sulfide/sulfate patina layer.

-

Finally, a thin, breathable wax protective coating was applied to stabilize the patina without completely sealing the surface, allowing for slow, controlled aging.

-

-

Result: The fasteners provided a consistent, architect-desired antique appearance from day one and have aged uniformly over five years of coastal exposure without galvanic staining of the limestone or any unexpected corrosion failures, meeting both aesthetic and performance goals.

Conclusion: Engineering Durability from Stock to Finished Component

The pursuit of optimal corrosion resistance in brass CNC machined components is a holistic engineering endeavor that begins long before the first toolpath is generated. It encompasses informed alloy selection based on environmental chemistry, regulatory landscape, and mechanical demands. It requires machining strategies consciously designed to preserve metallurgical integrity, impart beneficial surface stresses, and eliminate contamination. And it often concludes with purposeful post-processing that either enhances the natural protective mechanisms of brass or applies a tailored barrier for extreme conditions.

At JLYPT CNC Machining, we treat corrosion resistance not as a simple material property checkbox, but as a performance characteristic to be engineered into a component through every phase of manufacture. Our expertise lies in navigating the complex interactions between composition, microstructure, machining-induced surface states, and operational environment. This integrated approach ensures that the brass components we produce deliver not just initial dimensional precision, but long-term reliability in the face of corrosive challenges.

Are you developing components where environmental durability is as critical as dimensional accuracy? Partner with a manufacturer who understands the science behind the surface. Contact our engineering team to discuss how we can optimize your brass components for enduring performance. Explore our full material and finishing capabilities at JLYPT CNC Machining Services.