The Invisible Foundation: How Precision CNC Machining Enables the Robotics Revolution

Introduction: The Unseen Precision Powering Modern Robotics

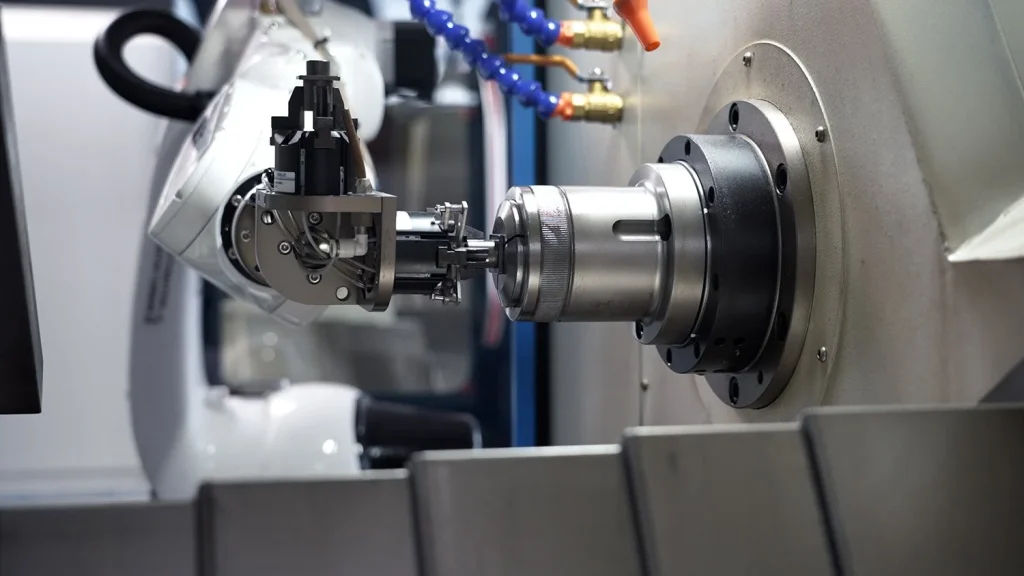

In an age where industrial cobots seamlessly collaborate with human workers, surgical robots perform sub-millimeter procedures, and autonomous mobile platforms navigate complex environments, the spotlight naturally falls on sophisticated software, advanced sensors, and artificial intelligence. However, beneath this layer of digital intelligence lies a critical, often overlooked physical foundation: the exquisitely precise mechanical components that translate electronic commands into flawless physical motion. This is the domain of CNC Robotics—not robotics that perform CNC machining, but the fundamental role of Computer Numerical Control machining in creating the very bones, joints, and actuators of the robots themselves. The performance, reliability, and precision of any robotic system are ultimately constrained by the quality of its machined parts.

At JLYPT, we operate at this critical intersection, serving as a foundational manufacturing partner to the robotics industry. We specialize in the high-volume production and prototyping of mission-critical robotic components, where tolerances are measured in microns, where material integrity is non-negotiable, and where geometric complexity defies conventional manufacturing. The development of a high-performance robotic arm is a symphony of mechanical engineering, and CNC machining writes the score. From the harmonic drive housings in a collaborative robot’s wrist to the lightweight, high-stiffness links of a SCARA arm, each component must embody a perfect balance of minimal mass, maximal strength, and absolute dimensional fidelity.

This technical analysis explores the indispensable synergy between advanced CNC machining and robotic innovation. We will dissect why materials like aerospace-grade aluminum 7075 and maraging steel are chosen for critical joints, how 5-axis simultaneous machining enables the integrated, compact designs essential for modern robotics, and the paramount importance of surface finish and dynamic balancing in high-speed rotary components. Through an exploration of kinematics, load dynamics, and real-world case studies, this guide demonstrates that partnering with a precision machining specialist is not a procurement step, but a strategic engineering collaboration essential for bringing next-generation robotic systems to life. Discover how our focused expertise in precision robotic parts machining transforms complex designs into reliable, high-performance mechanical reality.

The Mechanical Imperative: Why Robotics Demand Uncompromising Precision

Robotics is the engineering of controlled motion. Every aspect of a robot’s performance—its repeatability, accuracy, speed, payload capacity, and longevity—is directly dictated by the precision and quality of its mechanical structure. Off-the-shelf or generically machined parts are incapable of meeting these extreme demands for several fundamental reasons.

Kinematic Chain Integrity and Error Stack-Up: A robotic arm is a serial chain of links connected by joints. The positional error of the robot’s end-effector (the “tool tip”) is the cumulative sum of errors from every joint and link in the chain. This phenomenon, known as error stack-up, means that a tiny angular deviation in a single joint bearing seat or a minute parallelism error in a link can be magnified into a significant positional inaccuracy at the end of a long arm. CNC machining, capable of holding positional tolerances within ±0.01 mm and angular tolerances within a few arc-minutes, is the only process that can minimize these errors at the source, ensuring the kinematic model programmed into the robot’s controller matches its physical reality.

Structural Dynamics and Vibration Damping: High-speed robots are susceptible to vibration, which degulates precision, causes wear, and can lead to resonance failure. The natural frequency of a robot’s structure is a function of its stiffness and mass. Custom CNC-machined links can be designed with topologically optimized internal webbing and strategic material placement to maximize stiffness-to-weight ratio, thereby raising the natural frequency above the robot’s operational range. Furthermore, features like constrained layer damping channels can be machined into a part and filled with viscoelastic material to actively dissipate vibrational energy, a technique impossible with welded or cast structures.

Wear, Fatigue, and Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF): Industrial robots are expected to perform millions of cycles without failure. Components like gearbox housings, camera pivot shafts, and linear guide mounts are subject to constant cyclic loading. The superior fatigue strength of wrought aerospace alloys (like 7075-T6 aluminum) compared to cast alternatives, combined with a machined surface free of the porosity and inclusions common in castings, dramatically extends component life. A precisely machined Ra 0.4 µm surface finish on a bearing seat ensures optimal load distribution and prevents premature brinelling (surface denting), directly contributing to a higher MTBF.

Thermal Stability and Precision Under Load: Robots generate heat from motors, drives, and friction. Different materials expand at different rates (Coefficient of Thermal Expansion, CTE). A robot calibrated at 20°C may drift at 35°C if its structure is thermally unstable. CNC machining allows for the use of materials with matched or low CTEs and the design of thermally symmetric structures that expand uniformly, minimizing thermal drift. Similarly, finite element analysis (FEA)-informed machining can reinforce areas of high flexural or torsional load, ensuring the robot maintains its precision even when carrying its maximum payload.

Table 1: Robotic Performance Parameters Tied to Machining Precision

| Robotic Performance Metric | Key Influencing Mechanical Factor | Precision Machining Requirement | Consequence of Inadequate Machining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability & Accuracy | Cumulative error in joint axes alignment and link dimensions. | Sub-0.02 mm true position on bearing bores; ±0.01 mm on critical lengths. | End-effector fails to reach programmed points, causing process failure (e.g., mis-insertion). |

| Payload Capacity | Stiffness-to-weight ratio of arm links; strength of joint housings. | Topologically optimized, thin-wall structures from high-strength alloys (7075, Maraging Steel). | Arm deflects under load, reducing accuracy; risk of mechanical failure at stress concentrations. |

| Maximum Speed & Acceleration | Mass moment of inertia of rotating links; structural damping. | Internal lightweighting pockets; balanced rotary assemblies; integrated damping design. | Speed limited by vibration; excessive energy consumption; potential for destructive resonance. |

| Backlash & Hysteresis | Precision of gear meshes and bearing fits; stiffness of components. | H7/g6 or tighter tolerance fits on shafts and housings; ultra-flaw bearing seat surfaces. | “Sloppy” movement, lost motion, poor force control, and reduced positional precision. |

| Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) | Fatigue life of materials; wear resistance of bearing surfaces. | Use of certified, high-fatigue alloys; super-finished surfaces (Ra < 0.2 µm) on wear surfaces. | Unplanned downtime, premature bearing failure, crack propagation in high-stress areas. |

| Thermal Stability | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) matching and symmetry. | Use of low-CTE materials (Invar, ceramic composites) for metrology frames; symmetrical design. | Drift in calibration with temperature changes, requiring frequent re-teaching. |

The Material Science of Motion: Engineering Substrates for Robotic Components

Selecting the correct material is a foundational decision that balances mechanical properties, manufacturability, and cost for each specific robotic function.

Aluminum Alloys: The Core of Kinematic Structures

-

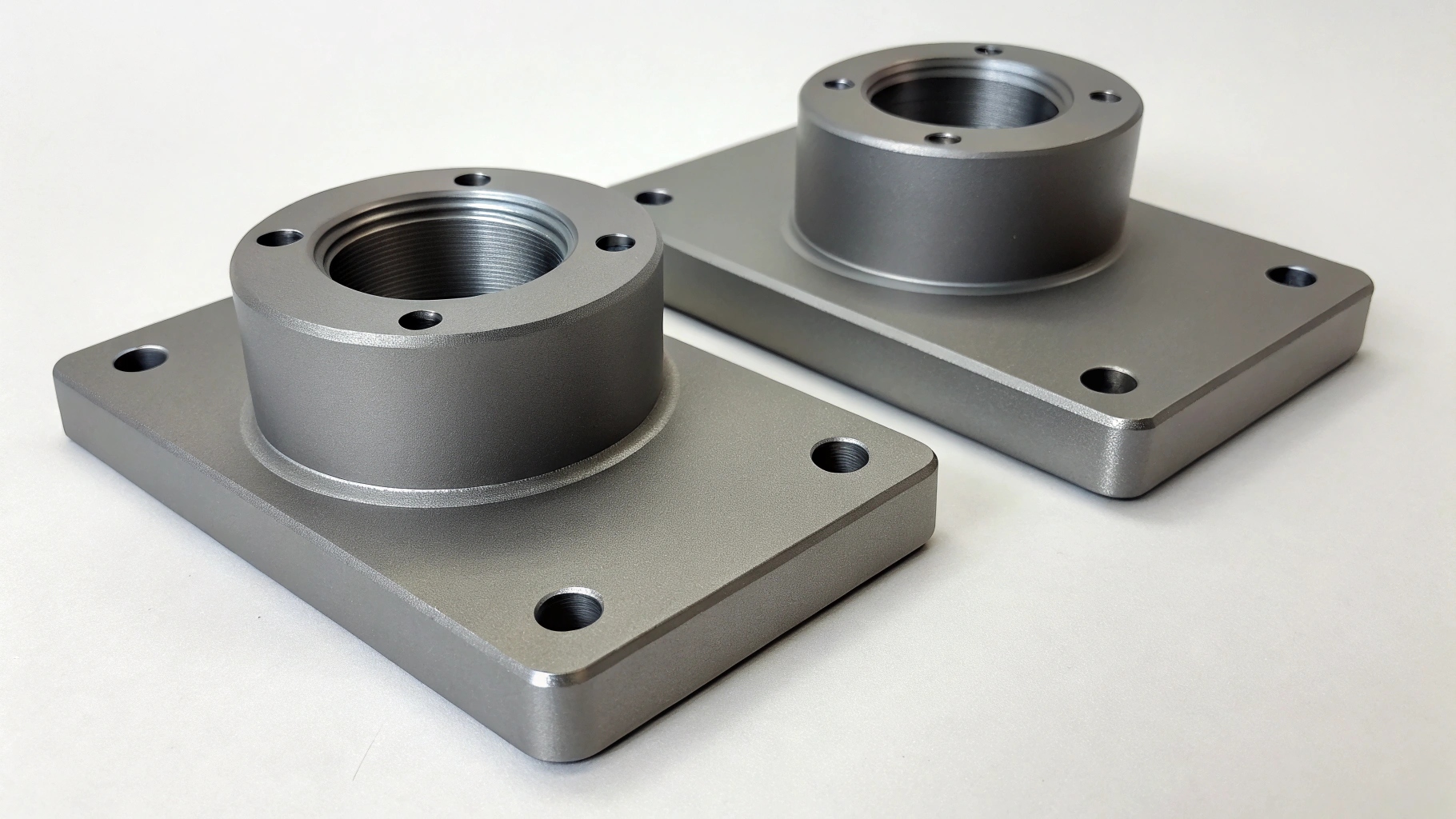

6061-T6: The workhorse for non-critical structural brackets, enclosures, and mounting plates. Offers good machinability, weldability, and anodizability at a lower cost.

-

7075-T6: The premium choice for high-stress dynamic structures. Its very high tensile strength (≥ 500 MPa) and good fatigue resistance make it ideal for robot arm links, joint housings, and end-effector adapters where stiffness and low weight are paramount. It is typically joined with aerospace-grade fasteners rather than welding.

-

6082-T6: Similar to 6061 but with slightly better mechanical properties, often specified in European robotic designs.

Steel Alloys: For Strength, Wear, and Precision

-

4140/4340 Alloy Steel (QT): Used for high-strength shafts, pins, and gears where hardness (after heat treatment) and core strength are required. Often chrome plated or nitrided for wear resistance.

-

Stainless Steel (304, 316, 17-4PH): Essential for food-grade, medical, or cleanroom robots due to corrosion resistance. 17-4PH (precipitation hardening) offers high strength and can be machined before a final age-hardening treatment to achieve high hardness with minimal distortion.

-

Maraging Steel (e.g., Grade 300): An ultra-high-strength steel (ultimate tensile strength can exceed 2000 MPa) that is machined in a soft, solution-annealed state and then age-hardened. Used for critical, highly stressed components in high-performance robots, such as harmonic drive flexsplines or high-torque drive shafts.

Specialty Alloys and Composites:

-

Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V): Used where an exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance justify its high cost and difficult machinability. Applications include aerospace robotics and implants for surgical robots.

-

Invar (Fe-Ni36%): A nickel-iron alloy with an exceptionally low CTE. Used for metrology frames and reference structures within ultra-precision robots (e.g., semiconductor wafer handlers) where thermal stability is absolutely critical.

-

Engineered Polymers (PEEK, VESPEL): Used for electrical insulation, low-friction bushings, and components in vacuum or high-purity environments. They can be machined to high tolerances and offer unique chemical resistance.

Table 2: Robotic Component Material Selection Matrix

| Robotic Component | Primary Loads & Environment | Optimal Material Choices | Key Rationale & Machining Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robot Arm Link (e.g., for 6-axis arm) | Bending, Torsion, Vibrational; needs max stiffness/weight. | 7075-T6 Aluminum (standard), Carbon Fiber Composite (high-end). | Topological optimization via 5-axis machining is key. Balance stiffness with cable routing channels. |

| Rotary Joint Housing | High bearing preload, cyclic stress; contains precision gears/bearings. | 7075-T6 Aluminum, Ductile Iron (for very large joints). | Requires exceptional bore roundness and perpendicularity for bearing life. Often a complex 5-axis part. |

| Harmonic Drive Components (Cup, Flexspline) | Extreme cyclic elastic deformation, high torque. | Maraging Steel, Specialty Stainless Steels. | Demands micro-machining precision, superb surface finish, and stress-free machining prior to heat treat. |

| Linear Slide Carriage / Gantry Cross-beam | Bending under moving load, need for straightness. | 6082/7075 Aluminum (anodized), Granite (for ultra-precision). | Long-part machining capability is critical. Requires stress-relieved stock and balanced machining passes. |

| End-Effector (Gripper) Jaws | Pinching/Crushing force, abrasive wear. | Tool Steel (D2, A2) hardened, Stainless Steel with hard coating. | Machined soft, then heat-treated and ground. Requires precise geometry for gripping force profile. |

| Sensor & Camera Mounting Bracket | Minimal deflection, vibration isolation. | 6061-T6 (for cost), Magnesium (for ultra-light). | Damping features (e.g., tuned mass dampers) can be integrated into the machined design. |

| Base Frame / Pedestal | Static compression, damping of whole-arm vibration. | Welded Steel (low-cost), Granite Composite (high-precision). | While often welded, critical mounting interfaces are machined in situ or with a CNC mill for flatness. |

Advanced Machining Paradigms for Robotic Components

Producing robotic parts requires more than standard milling; it demands specialized strategies to meet unique challenges of precision, complexity, and surface integrity.

5-Axis Simultaneous Machining: Enabling Compact, Integrated Designs

Modern robots prioritize a small footprint and envelope. 5-axis machining is essential for creating complex, monolithic parts that consolidate multiple functions. For example, a single robot wrist unit can be machined from a solid block to incorporate motor mounts, gearbox interfaces, a pass-through for cables/air, and mounting features for the next link—all in one setup. This eliminates assembly errors and maximizes stiffness. The ability to machine compound angles and deep cavities with a short tool is fundamental to this integrated design philosophy.

Micromachining for Miniature and Medical Robotics:

The field of surgical and micro-assembly robots requires features with tolerances in the single-digit micron range. Micromachining using small-diameter end mills (down to 0.1 mm) on high-speed, high-stability CNC platforms is used to create intricate jaws for micro-forceps, gears for planetary gearheads, and fluid channels in surgical tools. This demands specialized tooling, advanced CAM programming for toolpath smoothing, and often a vibration-damped machine tool environment.

Hard Turning and Grinding for Post-Heat-Treat Precision:

Many steel components are heat-treated to achieve high hardness (>45 HRC). Machining these hardened materials requires hard turning with cubic boron nitride (CBN) inserts or precision grinding. This is a critical step for final-sizing hardened shafts, bearing races machined directly into a housing, and gear teeth, achieving the final dimensional accuracy and mirror-like surface finish necessary for smooth, low-backlash operation.

In-Process Metrology and Closed-Loop Machining:

For the most critical components, integrating probing systems directly into the machining process creates a closed-loop manufacturing cell. A touch probe can measure the part after roughing and semi-finishing, and the CNC controller can automatically adjust the tool offsets for the final finishing pass to compensate for any detected tool wear or material movement. This ensures that every part, even in a small batch, meets the exact same specification—a cornerstone of quality in robotics manufacturing.

Case Studies: Precision Machining Solving Robotic Design Challenges

Case Study 1: Collaborative Robot (Cobot) Forearm Assembly

-

Challenge: A cobot manufacturer needed a forearm housing that was extremely lightweight to maximize payload capacity, yet incredibly stiff to ensure precision. It also had to neatly route multiple motor power cables, encoder wires, and an Ethernet cable internally from the elbow to the wrist, with quick-connect functionality.

-

JLYPT Solution: We designed and manufactured a monolithic forearm housing from 7075-T6. Using 5-axis machining, we created:

-

A topologically optimized external shell with thick walls only around bearing housings and thin walls elsewhere.

-

Internal segmented channels with smooth radii to guide and protect cable bundles without sharp bends.

-

Integrated mounting bosses and precision pilot features for the wrist joint assembly and cable connector blocks.

-

The part was hardcoat anodized for wear resistance at joint interfaces. The single-piece construction was 25% lighter and 40% stiffer in torsion than the previous two-piece bolted design, directly increasing the cobot’s performance specifications and simplifying assembly.

-

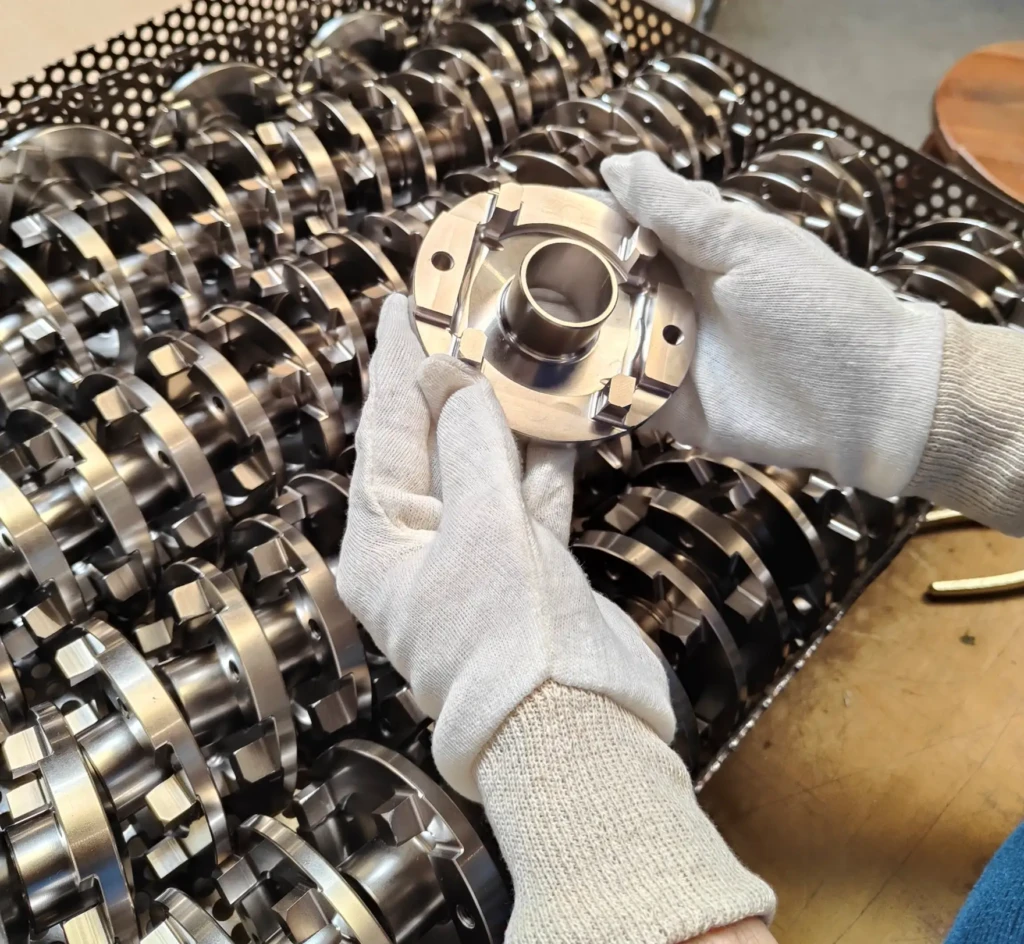

Case Study 2: Delta Parallel Robot Central Platform

-

Challenge: The heart of a high-speed Delta robot for pick-and-place is its central, moving platform. This part must be perfectly rigid, dynamically balanced, and have three pairs of perfectly parallel and equidistant bearing mounts for the carbon fiber rods. Any error here causes binding, vibration, and catastrophic wear.

-

JLYPT Solution: We CNC-machined the platform from a single piece of 6082-T6 aluminum. The key was a single-setup machining strategy on a high-precision 5-axis mill:

-

All three pairs of bearing housings were bored in the same setup, guaranteeing their mutual parallelism and angular position relative to the central tool mounting plate.

-

Kinematic coupling features (three hemispherical seats) were machined into the bottom for a deterministic, repeatable interface with the end-effector.

-

The part was dynamically balanced by machining small pockets in strategic locations on the backside after an initial spin test.

-

The result was a platform that enabled the robot to achieve its full rated speed of 150 picks/minute with a repeatability of ±0.02 mm, with zero measurable binding over millions of cycles.

-

Case Study 3: Surgical Robot Wrist Actuation Unit

-

Challenge: A developer of a minimally invasive surgical robot required a miniature, sealed wrist mechanism that provided two degrees of freedom (pitch and yaw) at the surgical end-effector. The housing had to be biocompatible, sterilizable, and contain tiny, high-precision gears and bearings. The entire assembly needed to fit within a cylinder 12mm in diameter.

-

JLYPT Solution: This project required micro-precision machining and advanced materials.

-

The main housing and internal bevel gears were machined from Ti-6Al-4V ELI (Grade 23) titanium for biocompatibility and strength.

-

Using a Swiss-type CNC lathe with live tooling and a 5-axis micromachining center, we produced gears with module 0.15 and housing bores with tolerances of +0.004/-0.000 mm.

-

All parts underwent a stringent vibratory finishing and electropolishing process to achieve a flawless, deburred surface suitable for sterilization and to prevent biofilm adhesion.

-

The final assembly, performed in a cleanroom, provided smooth, backlash-free motion, enabling the precise articulation required for complex surgical tasks through a tiny incision.

-

Conclusion: Machining as a Strategic Enabler in Robotics

The trajectory of robotics—toward greater speed, intelligence, collaboration, and miniaturization—is fundamentally linked to advances in precision manufacturing. The dream of a perfectly responsive, reliable, and capable robot is mechanically grounded in the reality of micron-level tolerances, optimized material structures, and flawless surface finishes. CNC machining is not merely a way to make robot parts; it is the essential discipline that allows the theoretical performance of a robotic design to be realized in the physical world.

Choosing a manufacturing partner for robotic components, therefore, is a decision of strategic importance. It requires a vendor who not only operates advanced machine tools but who understands robotic kinematics, structural dynamics, and the relentless pursuit of quality necessary for millions of reliable cycles. At JLYPT, we have built our practice on this deep technical partnership, providing the engineering insight and manufacturing excellence that turns groundbreaking robotic concepts into dependable, high-performance systems.

Are you developing the next generation of robotic technology? Partner with a manufacturer who understands the critical foundation your innovation rests upon. Engage with our engineering team to discuss how precision CNC machining can optimize your design for performance, reliability, and manufacturability. From prototype to production volume, we provide the expertise to build the future of motion. Begin the conversation at JLYPT Precision Robotic Parts Machining.