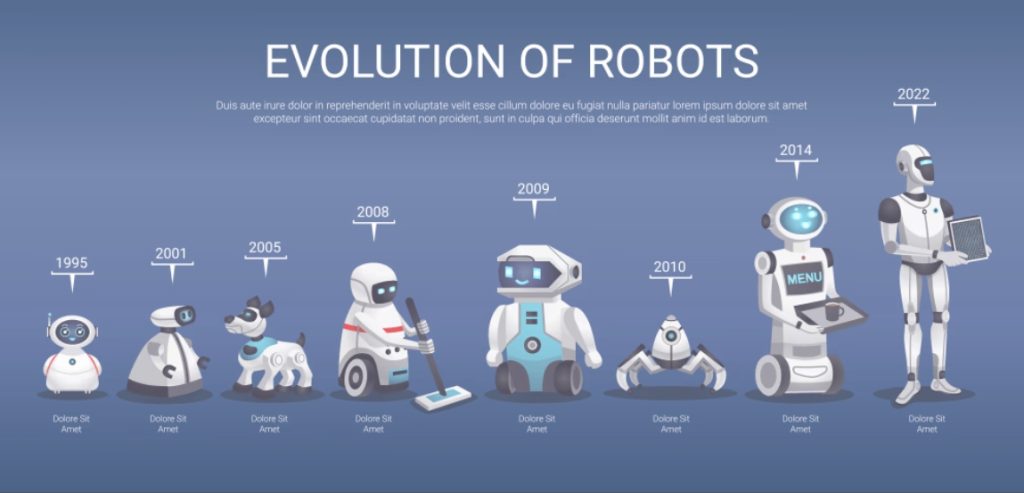

The Evolution of Excellence: A Historical Journey of Robotics in Manufacturing

The relentless pursuit of precision, efficiency, and scalability has defined manufacturing for centuries. Today, this pursuit finds its most advanced expression in the seamless integration of robotics with high-precision CNC machining. At JLYPT, where we operate at the forefront of precision engineering with our 5-axis CNC milling and advanced EDM services, we recognize that our present capabilities are built upon a rich historical foundation. Understanding the history of robotics in manufacturing is not an academic exercise; it is crucial context for appreciating the transformative power of modern automation and for making strategic decisions about the future of production.

This detailed exploration traces the history of robotics in manufacturing from its mechanical precursors to the intelligent, collaborative systems defining Industry 4.0. We will chart the key technological breakthroughs, examine their direct impact on machining processes, and project future trends. For manufacturers and engineers, this journey illustrates how far we have come and illuminates the path toward even greater innovation in precision manufacturing.

Chapter 1: The Pre-Robotic Era and Mechanical Precursors (Pre-1950s)

Before the advent of programmable robots, manufacturing automation was achieved through rigid, mechanical means. The foundational concepts of automated motion were established in this era, setting the stage for the robotic revolution.

-

The Industrial Revolution and Transfer Machines: The 18th and 19th centuries introduced powered machinery. By the early 20th century, dedicated transfer machines were developed for high-volume industries like automotive. These machines performed a sequence of operations (drilling, tapping, milling) as a workpiece moved along a fixed path on a conveyor or indexing table. While highly efficient for a single task, they were incredibly inflexible. Changing a part design required a complete and costly overhaul of the mechanical system. This rigidity highlighted the need for a more programmable approach to automation.

-

The Birth of Numerical Control (NC): The true progenitor of modern industrial robotics was the development of Numerical Control (NC) in the late 1940s and 1950s. Pioneered by John T. Parsons and MIT, NC machines used punched tape to store coded instructions (G-code precursors) that directed the movement of a machine tool. For the first time, machine behavior could be changed by altering a program rather than its physical components. This breakthrough introduced the core principle of software-defined manufacturing, separating the instructions from the machine hardware. The first commercially available NC mill, the Cincinnati Milacron Hydrotel in 1952, demonstrated the potential for producing complex, variable parts without custom tooling.

This era established the critical dichotomy between dedicated automation (cheap per unit, expensive to change) and programmable automation (versatile but initially slow and complex). The stage was set for a machine that could combine the programmability of NC with the dexterity of a human arm.

Chapter 2: The First Generation – Birth of the Programmable Arm (1950s-1970s)

This period witnessed the transition from concept to commercial reality, giving birth to the first true industrial robots.

-

George Devol and the “Unimate”: In 1954, George Devol filed a patent for a “Programmed Article Transfer,” a device widely recognized as the blueprint for the first industrial robot. His company, Unimation, brought this to life with the Unimate. In 1961, the first Unimate was installed at a General Motors die-casting plant in New Jersey. Its task was simple yet revolutionary: to extract hot die-cast parts and stack them. The Unimate was a hydraulically powered, point-to-point controlled arm that stored sequences of motions on a magnetic drum.

-

Early Applications and Technological Limits: These first-generation robots were primarily used for material handling—die casting, spot welding, and palletizing. They were large, expensive, and required significant safety caging. Their programming was tedious, often done by physically leading the arm through a sequence (a technique later formalized as teach pendant programming). They operated in a sequence-controlled manner with limited or no external sensory feedback, making them suitable only for highly structured, predictable environments. Their impact was profound: they proved that machines could perform dull, dirty, and dangerous tasks, improving both worker safety and consistency in specific, high-volume applications.

Chapter 3: The Second Generation – The Rise of Precision and Sensors (1970s-1990s)

The 1970s and 80s saw robots evolve from simple material movers into more sophisticated tools capable of precise, sensor-guided work. This generation saw the convergence of robotics with advancing CNC technology.

-

The Microprocessor Revolution: The introduction of the microprocessor was the catalyst. It replaced clunky drum memory with digital computers, enabling more complex path control, data storage, and the beginning of offline programming. Robots could now follow continuous paths, not just move between points. This was essential for applications like spray painting and arc welding, where smooth, precise motion was required.

-

Integration with CNC Machining: This era marked the first meaningful intersection of robotics and precision machining. Robots began to be used for machine tending—loading raw billets into CNC mills and lathes and unloading finished parts. This boosted machine utilization by allowing CNC equipment to run during breaks and overnight. Furthermore, robots themselves began to be used as programmable platforms for deburring and grinding, using basic force feedback to maintain contact with a part’s edge. The development of electric servo motors provided cleaner, more precise, and more repeatable motion than hydraulic systems, improving robot accuracy.

-

The Emergence of Vision and Tactile Sensing: For robots to move beyond pre-programmed cages, they needed to perceive their environment. Basic 2D vision systems and simple tactile sensors began to appear in research and high-end applications. This allowed for early forms of adaptive control, such as a robot using a camera to locate a part on a conveyor before picking it up. The International Federation of Robotics (IFR) was founded in 1987, signifying the maturation of robotics as a global industry.

Table 1: The Generational Evolution of Industrial Robotics

| Generation | Approx. Timeframe | Defining Technology | Control Paradigm | Primary Applications | Relationship to CNC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 1960s-1970s | Hydraulic actuators, magnetic drum memory. | Point-to-point, sequence control. | Die casting, heavy material handling, spot welding. | Separate, parallel technology. |

| Second | 1970s-1990s | Microprocessor, electric servos, early sensors. | Continuous path, rudimentary servo control. | Spray painting, arc welding, basic machine tending, palletizing. | Initial integration for loading/unloading. |

| Third | 1990s-2010s | Advanced sensors, PC-based control, networking. | Sensor-guided, path-adaptive, networked control. | Precision assembly, complex machining tending, detailed finishing. | Tight integration; robots as part of flexible manufacturing cells (FMC). |

| Fourth (Current) | 2010s-Present | AI/ML, cloud computing, advanced force/torque control, cobot design. | Cognitive, collaborative, cloud-optimized. | Human-robot collaboration (HRC), AI-driven quality inspection, adaptive machining. | Symbiotic fusion; robots perform secondary ops and direct machining. |

Chapter 4: The Third Generation – Flexibility and System Integration (1990s-2010s)

Driven by the demands of globalization and the need for agile production, this era focused on making robots more flexible, easier to use, and integral parts of larger manufacturing systems.

-

Direct-Drive and Parallel Kinematics: Technological advances led to new robot structures. Direct-drive robots eliminated gearboxes, reducing friction and mechanical complexity for higher precision. Delta robots (parallel-link robots) were introduced, offering extremely high speed and precision in a small workspace, revolutionizing high-speed pick-and-place for electronics and pharmaceuticals.

-

The Age of Offline Programming and Simulation: As robot programs became more complex, teaching by pendant became a bottleneck. Offline Programming (OLP) software emerged, allowing engineers to program, simulate, and optimize robot cells on a computer. This digital twin approach minimized costly production downtime for commissioning and enabled the design of complex, multi-robot workcells.

-

Flexible Manufacturing Systems (FMS): Robots became the central nervous system of Flexible Manufacturing Systems. An FMS typically combined multiple CNC machines, a central pallet pool, and one or more robots or automated guided vehicles (AGVs) for material transport. The robot could dynamically route different parts to different machines based on the production schedule. This was the pinnacle of automated, high-mix, low-volume production, blending the flexibility of CNC with the material handling prowess of robotics. The widespread adoption of PLC and fieldbus networks (like PROFIBUS) enabled seamless communication between robots, CNCs, and other cell components.

Chapter 5: The Fourth Generation – The Cognitive and Collaborative Era (2010s-Present)

We are now in an era defined by intelligence, connectivity, and safety. Robots are no longer just tools; they are intelligent partners.

-

The Collaborative Robot (Cobot) Revolution: Introduced commercially in the late 2000s, collaborative robots are designed with inherent safety features (force/torque limiting, rounded edges, compliant joints) to work alongside humans without traditional safety fencing. This has democratized automation, making it viable for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and for tasks requiring close human-robot interaction, such as final assembly or delicate polishing. Cobots like those from Universal Robots can be deployed in a matter of hours, not weeks.

-

AI, Machine Learning, and Advanced Sensing: Modern robots are equipped with sophisticated 3D vision, laser scanning, and high-resolution force/torque sensors. When combined with Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), these systems enable unprecedented capabilities. Robots can now perform bin picking of randomly oriented parts, conduct AI-powered visual inspection with superhuman consistency, and execute adaptive machining where the toolpath is adjusted in real-time based on sensor feedback to compensate for material variances or achieve perfect surface finishes.

-

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and Cloud Robotics: Today’s robotic cells are nodes on a networked plant floor. Data on performance, maintenance needs, and quality metrics are streamed to the cloud via the IIoT. This enables predictive maintenance, fleet optimization, and cloud-based analytics. Cloud robotics allows for complex computation (like path planning for a massive digital twin) to be offloaded to powerful remote servers, and for one robot’s learned skill to be shared instantly with thousands of others.

Chapter 6: Case Studies in Robotic Evolution

Case Study 1: From Unimate to Adaptive Machining in Automotive

-

The Historical Step (1961): The first Unimate at General Motors performed a simple extract-and-stack task in a die-casting operation. It addressed a dangerous, hot, and repetitive job, proving the value of robots for ergonomics and consistency in ultra-high-volume settings.

-

The Modern Parallel: Today, a major automotive manufacturer uses AI-equipped robots for final quality assurance on CNC-machined transmission housings. A robot equipped with a high-resolution 3D scanner automatically inspects dozens of critical bore diameters, surface flatnesses, and thread profiles on every part. The data is logged for full traceability, and any out-of-tolerance condition triggers an alert. This represents the evolution from brute-force handling to intelligent, data-driven quality control, a direct descendant of the reliability-first principle established by the Unimate.

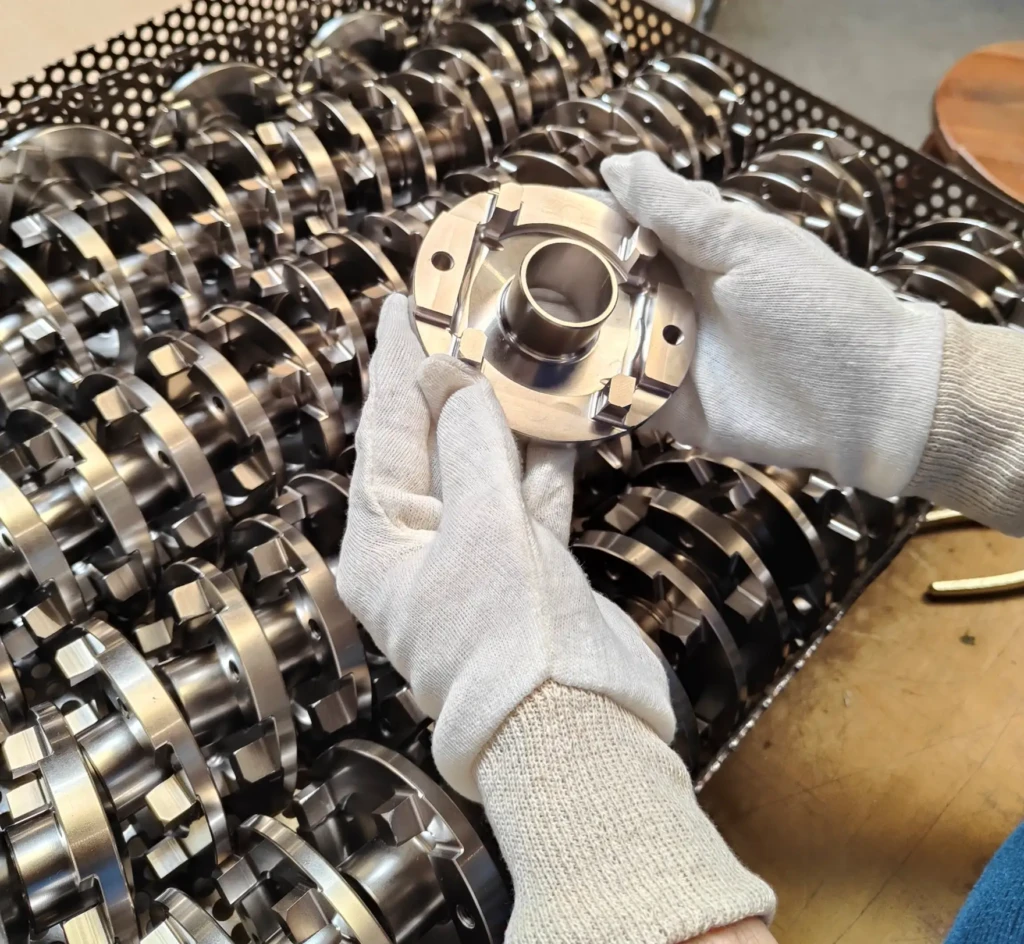

Case Study 2: The Evolution of a CNC Machining Cell

-

The 1980s Cell: A standalone CNC machining center operated by a skilled machinist. The worker loaded blanks, monitored the cycle, performed in-process checks, unloaded finished parts, and deburred them manually. Productivity was limited by human speed and endurance.

-

The 2000s FMS Cell: A Flexible Manufacturing System was installed. A gantry robot serviced two CNC mills and a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) from a central pallet pool. The robot loaded standardized fixtures, and the system could run untended for hours. Productivity soared, but the system was complex and required significant programming for each new part family.

-

The 2020s Cognitive Cell: A modern cell features a collaborative robot. The cobot, using built-in vision, picks raw blanks from a bin and loads them into a 5-axis CNC mill. After machining, it transfers the part to a force-controlled finishing station for adaptive deburring, then presents it to a vision system for final inspection. The human operator oversees multiple cells, handles complex setups, and performs exception management. This cell blends the flexibility of the 1980s machinist with the untended productivity of the 2000s FMS and the adaptive intelligence of modern AI.

Case Study 3: JLYPT and the Future-Proof Trajectory

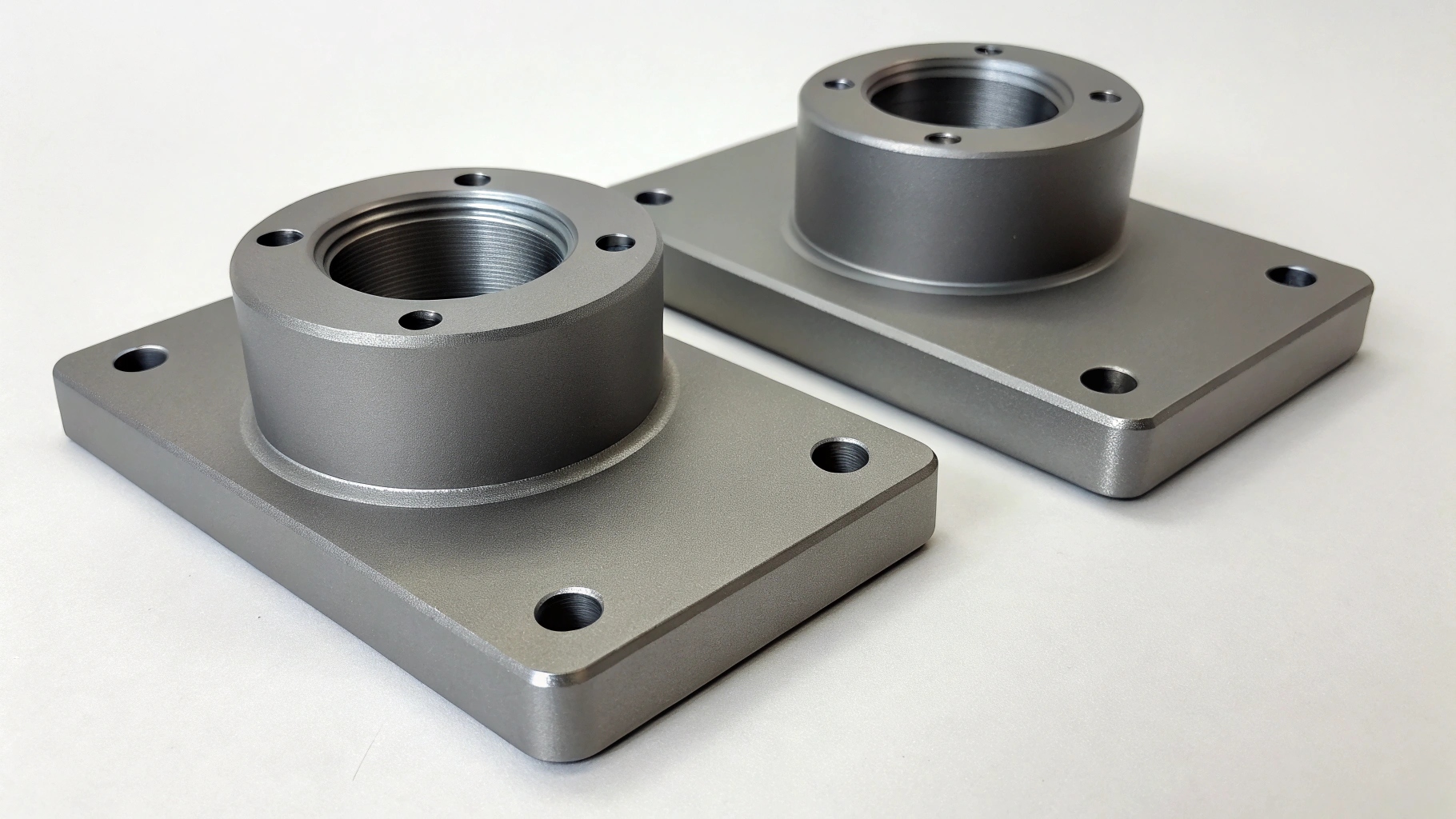

As a precision machining service provider, JLYPT’s own evolution mirrors the broader history of robotics in manufacturing. Starting with manual and basic CNC machinery, the progression to advanced 5-axis CNC milling and 7-axis hybrid machining represents the pinnacle of programmable precision in the “Third Generation” paradigm. Today, to stay competitive, JLYPT and similar leaders are integrating the technologies of the “Fourth Generation.”

-

Implementing Adaptive Finishing: By exploring robotic cells with force-feedback spindles for polishing and deburring, JLYPT can apply consistent, high-quality surface finishes (like the Ra 0.4µm achieved with EDM) to complex geometries, replicating skilled manual labor with unerring consistency.

-

Leveraging Data for Precision: The tight tolerances (as fine as ±0.005mm) demanded by aerospace and medical clients generate vast amounts of process data. The future lies in using AI to analyze this data, predicting tool wear before it affects tolerance, and automatically compensating in the CNC program—moving from statistical process control to predictive quality assurance.

-

Agile, Cobot-Assisted Production: For high-mix, low-volume prototyping, collaborative robots can be deployed to tend machines, manage post-process operations like cleaning or inspection, and allow human experts to focus on engineering and complex problem-solving. This creates a resilient, agile production model ready for the next shift in market demands.

Chapter 7: The Future Trajectory and Conclusion

The history of robotics in manufacturing points toward a future defined by even greater autonomy, resilience, and human-centric design.

-

Hyper-Automation and the Lights-Out Factory: The integration of robotics with AI, IIoT, and advanced materials will push toward fully autonomous “lights-out” manufacturing for certain processes, maximizing asset utilization.

-

Human-Robot Symbiosis: Cobots will become more aware and responsive. Advances in natural language processing (NLP) may allow machinists to program robots through speech or gesture, while augmented reality (AR) interfaces will overlay programming paths and diagnostic data directly onto the physical workcell.

-

Resilient and Sustainable Production: Robotics will be key to building resilient supply chains through localized, flexible micro-factories. AI-optimized processes will also minimize material waste and energy consumption, contributing to sustainable manufacturing.

The journey from the Unimate’s simple arm to today’s cognitive cobots demonstrates a clear arc: from replacing human muscle, to augmenting human skill, and now, to collaborating with human intelligence. For any manufacturer, this history underscores that robotics is not a singular project but a continuous strategic investment in capability, quality, and competitiveness.

At JLYPT, we are actively navigating this future. Our expertise in precision CNC machining services provides the essential foundation of accuracy and quality. By understanding and selectively integrating the next wave of robotic innovation, we ensure our manufacturing solutions are not just state-of-the-art today, but are engineered to evolve tomorrow.

Ready to build the next chapter of your manufacturing capabilities? Partner with JLYPT to leverage our precision machining expertise and forward-looking approach to integrated automation. Explore our capabilities and begin a conversation about your project at JLYPT CNC Machining Services.